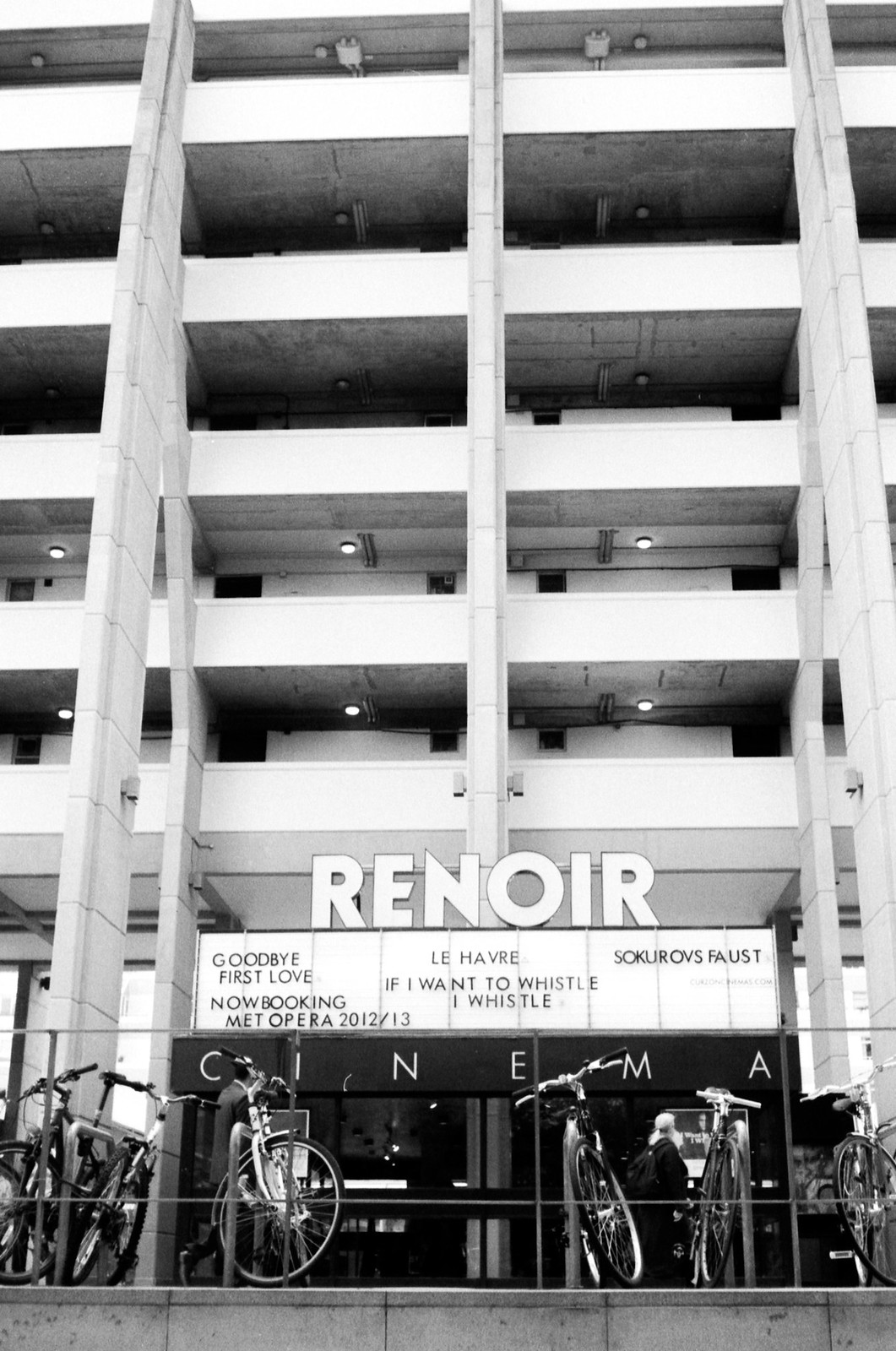

I didn’t think about it until during the film, but could there be any more appropriate location to watch High Rise than the Curzon Bloomsbury (née Renoir cinema) in the Brunswick Centre?

In Ben Wheatley’s superb adaptation of JG Ballard’s novel, his production designer Mark Tildesley has created a modernist* marvel of building. The way that the apartments are tiered in the film is very reminiscent of the much lower Brunswick Centre has tiering for its apartments, all in that same modernist style. The Brunswick Centre was designed by Patrick Hodgkinson who died very recently, and for who the centre was his most famous piece of work, long in gestation before finally opening in the ’70s and getting a revamp in the ’00s.

Recently the below-ground Renoir cinema has been modernised and overhauled, becoming the Curzon Bloomsbury. Although the cinema reopened a year ago, this was the first time I’d been back inside. The main reason for holding off was that the previous cinema had featured two screens, but following the 10 month refurbishment, it now features six screens. It does not take a genius to work out that all the screens are therefore now smaller than they were before, and when I see a film on the big screen, I tend to like that screen to be, well, big!

That’s not to say that the cinema was especially good in its old format. It was originally designed as a single 490 seat screen at the time of the centre’s opening in 1972, but as with so many cinemas in the 1980s, it was converted to become a two-screen cinema – essentially splitting the cinema down the middle. That left each of the two neighbouring screens uneven, with more seats on one side than the other. There were also pillars that you obviously couldn’t sit behind.

Now under its new name, it features six screens, of which only the “Premium Screen” is of a decent size with 177 seats. The other regular screens all seat between 28 and 30, making them feel a little closer to a hi-fi dealership’s screening room rather than a full blown cinema. They’re certainly plushly appointed and the chain has named the screens after now re-branded or closed cinemas from around London (Lumiere, Plaza, Phoenix and Minema). The Bertha Dochouse screen is actually larger at 55 seats. It’s a screen devoted documentaries and supported by a number of groups.

I saw High Rise in the 30 seat “Plaza” screen, and while I have no problems with the cinema itself – aside from a couple of late patrons casting shadows on half the screen as they spent too long finding their seats (another consequence of small screening rooms), I do wonder why I’m paying a premium to see a film on the big screen if home cinema screens are getting close to the same size. I exaggerate a little, but it’s an issue of mine. The seats are comfortable, and there are bars throughout, but paying £15 plus a £1 booking fee for such a small screen experience is galling.

But what about the film?

Well it’s really excellent. If you don’t like JG Ballard, then it won’t be your cup of tea, because this one of his dystopian future novels, in a believable future from around the time they were published. High Rise came out in 1975, and begins with Dr Robert Laing (Tom Hiddleston) moving into his new apartment mid-way up a brand new apartment block. For him and his fellow aspirant middle-class tenants in the block, this is a self-contained world. They have their own supermarket, a gym and a swimming pool.

But there’s a very rigid hierarchy, within the block. The higher up in the building you are, the greater your social standing. On the very top, in the penthouse, is the project’s architect, Anthony Royal (Jeremy Irons).

As Laing settles in, the high rise takes on a life of its own with an endless stream of parties to which you may or may not be invited. Laing befriends Charlotte (Sienna Miller) and her son who live just above him. But below him are Richard Wilder (Luke Evans) and his heavily pregnant wife Helen (Elizabeth Moss). Wilder is something of playboy, his wife seemingly acquiescent.

Higher up are people like the gynaecologist Pangbourne (James Purefoy), an actrees Ann Sheridan (Sienna Guillory) and Royal’s wife Ann (Keeley Hawes) who manages to keep a sheep and a horse on the top of the building.

Slowly and surely chaos begins to ensue as rubbish chutes are jammed, power-cuts hit the lower floors, and finally there is no water. Raiding parties look out for their own areas, yet there’s still a weird normality as some continue to head out of the building each day, walking out across the enormous car park to head off to their jobs.

The chaos gets worse, and there are assaults and all manner of debauchery. Yet somehow the building contains all of this. There’s an amusing sequence when a police car pulls up and Royal assures the policeman (a cameo from Neil Maskell who previously appeared in Wheatley’s Kill List) that everything’s fine. Revolt is in the air, and it’s uncertain how things will play out. The script is both very much in keeping with Ballard’s novel, whilst not afraid to diverge from it. Invariably there is a lot of compression, and fewer characters on fewer floors. And the timeframe seems compressed compared with the novel.

The performances are all excellent with Hiddleston almost gliding through the film, as Laing does in the book. Irons is right the grumpy architect who sort of knows his designed society is all collapsing around him. It’s fun seeing Hawes in yet another very different role – she’s currently very different in both the third series of Line of Fire, and as the mother in ITV’s new version of The Durrells.

You can’t separate the film from the superb production design. As well as the amazing architecture conjured up in CG, there interiors are beautifully delivered. I especially enjoyed seeing the supermarket with all the carefully labelled products (There’s an excellent article in Creative Review detailing this work) and signs.

And Clint Mansell’s soundtrack is also incredibly important, adding layers to the film. Beyond that there is incidental music such as muzack version of Abba’s SOS, later reprised into a fully-fledged song from Portishead. Sadly, it’s not included on the soundtrack, and the band prefers that you hear the song in the context of the film.

Finally, you can’t ignore Amy Jump, Wheatley’s partner in crime. The film credits her equally at the end, her writing, and he directing – the pair of them editing. The film is very truthful to the book, but Ballard is not the easiest author to adapt – there’s a sensibility to his work.

I loved this film, and can’t wait to watch it again and soak up some of the details.

* Or should that be brutalist? I’m afraid architectural doctrines are a little beyond me.