If there’s a genre films I really love, it’s screwball comedies.

His Girl Friday has always been one of my favourite films, and alongside Bringing Up Baby, epitomises what I love in the genre. The rat-a-tat dialogue, strong female characters, the prevalent design – lots of art deco, and in general the sheer delight. These were films that had to entertain a public suffering the great depression, and they were fast and made with flair.

With directors like Howard Hawks, George Stevens and Preston Sturges, and actors and actresses like Cary Grant, Carole Lombard, Irene Dunne and Claudette Colbert, alongside some sterling character actors in supporting roles, these were vibrant films that also addressed the prejudices of a nation.

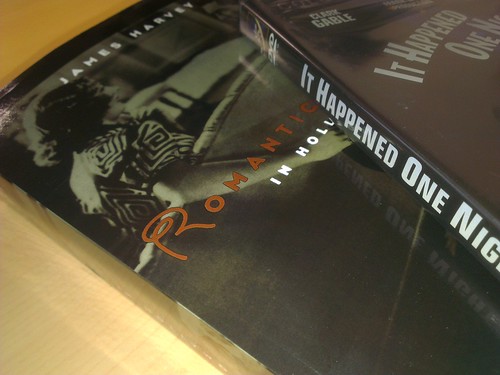

And as 2013 starts – Happy New Year – the BFI Southbank is running a season of these gems, including some lesser known titles that I’ve certainly never seen. Despite loving the genre, I’ve never really studied it and looked beyond the obvious films.

So as well as the aforementioned Bringing Up Baby and His Girl Friday, and other more popular films like The Philadelphia Story and Mr Deeds goes to town, some lesser known films are being screened.

According to the introduction from season curator Peter Swaab, arguably screwball could begin with Trouble in Paradise from 1932.

I’d never seen this, and as this BFI season starts in 1934 with the films usually considered the start of screwball era, I decided to look out this Ernst Lubitsch film that I feel I probably should be familiar with. Fortunately Eureka released it very recently on their excellent Masters of Cinema label, so I settled back to watch it on DVD.

Released in 1932, before the Hays Code came into place, it stars Herbert Marshall and Miriam Hopkins as essentially a pair of crooks who run into one another in a hotel in Venice. In due course the action moves to Paris where Kay Francis is Madame Colet, owner of a successful perfume company. Made in 1932, it perhaps addresses the depression more than most, with plenty of parts of the plot talking about the derpivations being suffered by the populace. There are multiple references to pay cuts, and the outrageousness of spending a fortune on a diamond encrusted bag, even if you’re able to afford it. None of this prevents the film still being set in glamourous locations and first class hotels of course. But that’s key to films of the period – these were fantasies to allow viewers to forget their day to day suffering.

As a pre-code film, there are lots of hints of out of wedlock relationships and double entendres, all meaning that the film does come across as a little more risqué than other films more frequently viewed on TV. This is another subject for another time, but the impact of that code is truly remarkable, and while clever filmmakers like Hitchcock worked around it – think of the kissing scene with Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant in Notorious, or the final shot of North by Northwest. Well worth watching.

At the BFI I’ve so far seen a couple of their screwball films. Twentieth Century probably counts of Howard Hawks’ first effort. The film was released in 1934 and stars John Barrymore as a superbly over-the-top theatrical impressario Oscar Jaffe who discovers Carole Lombard’s Mildred Plotka for his next stage production. After a tricky start, everything goes well until Plotka (or Lily Garland as Jaffe has renamed her) ups and leaves for Hollywood. The second part of the film is set a train – the Twentieth Century – from Chicago to New York, and that’s where the real fun begins, with the film at times being a farce. I particularly loved the dry lines Roscoe Karns is given as the permamently drunk right hand man of Jaffe. The film was based on a play by Charles Bruce Mullholland, but was rewritten by Ben Hecht and Charles McArthur, both of whom would later go on to work on Hawks’ His Girl Friday based on their own play.

Much less well known is Theodora Goes Wild which seems to have been Irene Dunne’s first screwball film, with her playing the title character. Living in a very conservative small town, she has also managed to hit the jackpot under the nomme de plume Caroline Adams with a sensational potboiler called “The Sinner” which is a runaway bestseller. But the book’s success does not go down well in her hometown, and when Melvyn Douglas – a louche book designer who works at her publisher’s – comes to town, the pack of cards looks like it might all come tumbling down. As Dunne’s character begins to shake off her small town shackles she begins to “go wild” and needless to say, the tables are turned later on in the film. The “moral” of the film seems to be that letting go, or “going wild” isn’t that bad a thing and everyone should loosen up a bit.

Interistingly, in both these latter films, drunkeness is played for laughs. Irene Dunne’s character wants to prove that she’s not square and drinks just about everyone else under the table when she goes out with her publisher and his wife. While the aforementioned Roscoe Karns character gets the best lines by virtue of being drunk the whole time (although the BFI notes to the film which include extracts of a Hawks interview suggest that it was Barrymore’s drinking that actually lost the production a day at one point). It feels that drinking with no “bad” consequences would be clamped down on a little more later.

I look forward to seeing plenty more films in this season, and perhaps a couple more on DVD too.

Screwball

Tags: