A week or so ago I popped in for a couple of sessions of an interesting music tech conference held in the BBC Radio Theatre called On the Beat.

One of the sessions included a presentation by the always interesting Will Page, Director of Economics at Spotify. He was examining the interaction of Spotify, Shazam, radio and sales in the case of the big international hit All About That Base by Meghan Trainor. And Spotify has just published the details from Page’s presentation. It’s well worth a read.

This was a track that was massive in the US before reaching the UK. What was particularly unusual was the delay in it being released to buy in the UK. Spotify made great play of that in the UK, having the track for a month and a half before consumers could buy it.

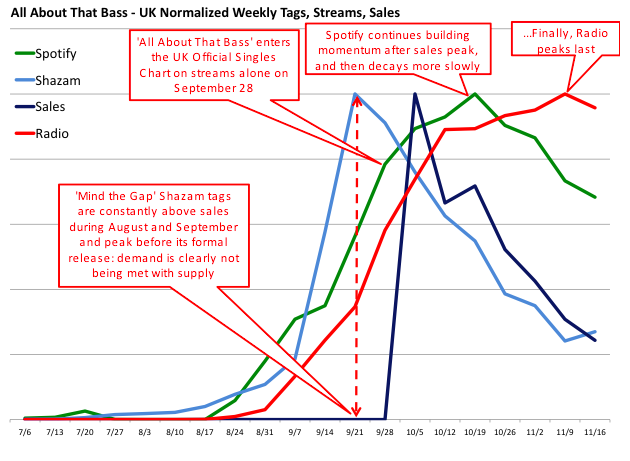

The key UK chart is probably this one:

The theory goes something like this. When people first hear a song they don’t know, they Shazam it, quite probably from some kind of broadcast media. Then they might either listen to it via Spotify or buy it somewhere like iTunes. But of course, if you can’t buy it, but can rent it on Spotify, then that’s what you do.

And the key thing with this track was that it was the first song to make the UK charts via streams alone. The chart rules changed this year, and 100 streams = 1 sale under the new rules.

Spotify’s case study very properly suggests that withholding the song from retail may have well damaged sales, and that the music industry should be borderless, not holding back tracks artificially on a territory by territory basis.

But I do have a little bit of an issue with the charts. You see, for market sensitivity reasons, you’ll notice that there are no numbers on the y axis. The numbers have all been normalised. The peak number of Shazams is not equal to the peak number of streams which is not equal to the peak sales. And most relevantly, nor is the amount of airplay listens coming from radio.

Because if you look at the chart above, it looks like radio came to the game very late with this release. Aside from a small number of Spotify listens very early on (before the track was on Spotify?), it’s Shazam that seems to lead the way. But what are people Shazam-ing?

They could be hearing it in clubs. That was the suggestion given in the room when someone raised a similar point. Other data shown at the conference by Shazam show very clearly that club tracks get heavily Shazam-ed at weekends. But put in context of a massive hit record like this, I’m unconvinced it’s purely clubs.

But I wonder if the detail isn’t in the normalisation? Radio gets thoroughly flattened by the process. But a handful of plays on some key shows when the chart is “normalised” might appear hidden. Because without the artificial flattening, I’m certain that radio would have the biggest peak, followed by streaming/Spotify, then sales and then Shazam. And those might be quite substantial differences in scale (See my piece on possible artist earnings from radio to get an idea of that scale).

So a few key plays on Radio 1 or Kiss early on, may have led to a lot of Shazam-ing among music influencers, which certainly then meant a lot of Spotify listening (since that was one of the few places you could hear the track), before sales only came in pretty late in the day once the label had released.

Because if people are Shazam-ing your song, they’re hearing it somewhere without the ability to find out the track’s name (i.e. probably not online). And clubs aside, that usually means radio.

I wouldn’t deny that radio, like the label, was late to the party with this track. However radio always stays with a song longer than sales do (“I’ve already bought the track, but that doesn’t mean I don’t like to hear it”). But I wonder if it wasn’t early as well?