I was recently talking to a some colleagues at work about one of my favourite films of all time, the classic Howard Hawks screwball comedy, Bringing Up Baby.

Made in 1938, it stars two of Hollywood’s biggest ever stars, Kathryn Hepburn and Cary Grant, both giving terrific performances in a classic of the genre.

How can we see this film I was asked by my colleagues?

Both of them have Netflix and Amazon, and one has Now TV from Sky. Needless to say that Bringing Up Baby is on none of these platforms. It’s not available to buy in the UK iTunes Store, it’s not on the Google Play Store, and nor is it available to buy from Amazon’s streaming platform.

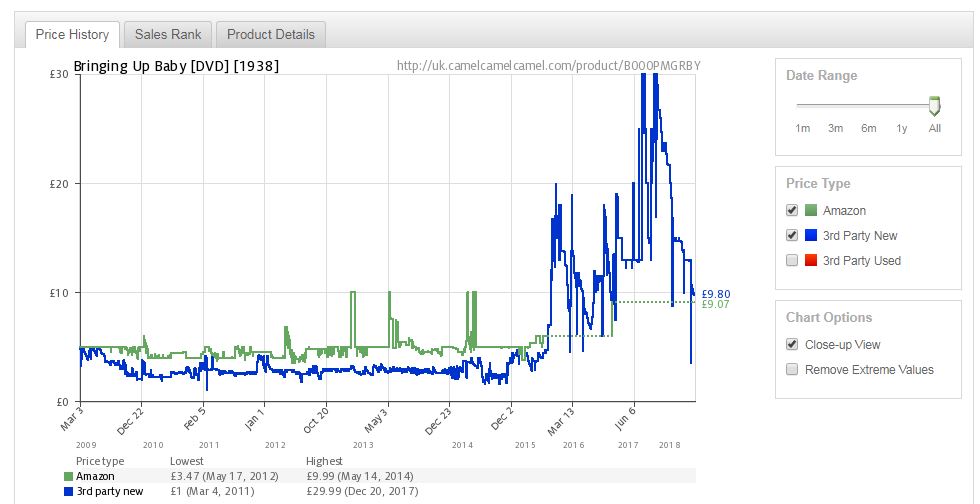

There is a DVD available on Amazon, but the price has been fluctuating wildly. When I looked for it at the time of my conversation it was £26.89, and according to Camelcamelcamel has been retailing for as much as £30! It has now dropped back to £11.99.

That’s for a third party “Fufilled by Amazon” copy.

There are cheaper non-UK copies of the film on DVD, but they’re mostly NTSC, and are sometimes region-locked. That’s assuming that either of my colleagues still have a DVD player at all.

Bringing Up Baby is listed by the American Film Institute as one of the 100 Greatest Movies of All Time. But you essentially it’s incredibly hard to get a legal copy of it in the UK in 2018.

That hasn’t always been the case. That disc that’s being sold for nearly £27 was released by Universal Home Video in the UK in 2007, and for many years it sold for between £2 and £5. Judging from the chart at CamelCamelCamel, sometime around late 2014, the title went out of print at Universal and over time the dwindling remaining stock in circulation saw its price rise.

But in recent years, DVD sales have fallen off a cliff, and there are fewer and fewer retail outlets selling physical discs. Aside from Amazon, there are just HMV and Fopp left on the High Street – both with many fewer stores than in years gone by. Big releases still sell decent quantities via supermarkets. But with the exception of specialist mail order sites and labels, that’s about it.

The answer should be that all these titles have moved to digital. And with the bigger budget blockbusters, that’s been the case. But significant chunks of the archive have not been uploaded.

They’ve not been leased to the streaming giants like Netflix or Amazon Prime, and nor have they been made available to buy from the Google Play Store or Apple iTunes Store.

It’s as though we’ve entered a “dark ages” period, where unless the title was made recently, it’s lost to us and is no longer available. It feels as though there are fewer titles available to watch than DVD and Blu Rays sales peak in 2007/8.

The chart above, based on data from a Netflix scraping website, shows you the number of films, by release year that Netflix UK offers subscribers. Obviously this data will change daily, but at the time of writing, of the 3,522 films with release dates (all bar one film), 73% were made 2010 onwards.

This second chart summarises this by decade.

To be specific, there is one film from the 1920s on Netflix – Cecil B DeMille’s first version of The Ten Commandments.

There are zero films from the 1930s, and the 17 films from the 1940s are nearly all war films, I believe mostly to accompany a 2017 three part WWII documentary from Steven Spielberg, Five Came Back. You won’t find any Oscar Best Picture winners from this period on Netflix.

There are fewer films from the 1950s than the 1940s – just 13. But they’re all minor titles with only Some Like It Hot and Touch of Evil being especially notable.

From there, things slowly improve, with more classics finding their way into the catalogue. But it’s a lean selection.

(I should again emphasise that I’m critiquing the UK selection. US reader may well have a deeper and better stocked catalogue.)

While as a Netflix subscriber, I can and will moan about the selection, they’ve never set themselves up as a classic movie service. And to an ever greater extent, they’re moving towards owning more of their own properties and relying less on renting catalogue material from studios. So I expect that the paltry fare currently offered will actually further diminish over time.

Now it’s true – there is the BFI Player. And while researching this piece, I came across FilmStruck which notably has access to the Criterion Collection (although the latter’s UK catalogue is vastly smaller than its US cousin). But today we learnt that Warner Media is shutting down FilmStruck. Whether on its own it was uneconomical, or whether this is more a move by TimeWarner ahead of it building a more singular streaming vision led by HBO; we don’t yet know.

Both the BFI Player and FilmStruck are/was rental offerings. And from the abrupt closure of FilmStruck, we can see the issue. A corporate change of direction and suddenly there’s no place in the market for classic films.

Also streaming services invariably don’t have the range or consistency of offerings. A film that there this month is gone next month. If I want to see The Maltese Falcon, I’m going to have search a lot of different services to see who has it available – if anyone.

Another operator who specialises in quality classic films, MUBI, goes out of its way to minimise choice to a rolling list of 30 films that sees one title added and one removed every day. Intelligent cinema, yes, but an incredibly limited choice. If I’ve got something in mind to see, these aren’t necessarily the places I’d go.

Films are less of an overall offering of the bigger free-to-air channels – BBC2 is more likely to be showing repeats of Bargain Hunt than an old black and white film. And while we have got the welcome addition of Talking Pictures TV, the quality of the prints they show can vary (Seriously! Get the Criterion Collection Blu Ray of His Girl Friday, or the Columbia Classics DVD. Don’t watch the “public domain” copy that Talking Pictures TV uses, or that can be found on Amazon), and they have a relatively low bit-rate for broadcasting which doesn’t help either.

Other channels tend to keep the same popular fare repeated on hard rotation. You’ll know when you hit ITV4 if you go channel surfing at 9pm.

The problem is that the retail model made sense for a lot of studios. Over the years, they dug deeper into their libraries and they released just about anything they thought they could sell. Costs were relatively contained, and even manufacture and storage costs were lowered as just-in-time manufacture of discs became more achievable. The Warner Archive Collection is a great example of this.

In theory, that should have followed through to the digital sales stores of iTunes, Amazon and Google. If you’ve gone to the ‘trouble’ of digitising a film you own the rights to, why wouldn’t you just upload copies to iTunes, Amazon, Google Play Movies and others? Set a price and watch those sales trickle in.

Sure, nobody’s going to get rich overnight, but you’re working your assets, and fulfilling demand.

Yet for some reason, it doesn’t seem to have been worthwhile for studios to do any of this. It’s hard to understand. Unlike physical products, there’s no warehousing cost, or indeed physical manufacture of any sort. You take a digital asset, upload it to the sites and even if the film only earns a few dollars a year, that’s money that would be left on the table otherwise. But there are a vast range of films, including some relatively recent titles, that simply haven’t been uploaded to these services.

The trouble is that in the meantime, consumers have moved increasingly towards subscription models for all their entertainment. They rent their music, and they rent their TV and movies. And there isn’t necessarily room for all that many competing services. There is ‘subscription fatigue’ when you realise just how many things you’re subscribed to.

The real difference between the movie/TV model and music is that Spotify and Apple Music make all the music available (or nearly all, anyway). Now that just about all the biggest holdouts have given in, you don’t tend to see albums or artists drift in and out of the service the way movies do on Netflix. I know that I’ll be able to hear The Beatles on Spotify today, tomorrow and next year (probably).

What I don’t know is where I can watch Inception, or Star Wars, or Psycho, or Gone with the Wind, or Bringing Up Baby on any given day. Are they on Netflix or Amazon? Maybe. Maybe not.

For at least one of those films, I know it’s not on any of the services.

And that’s surely a problem. I shouldn’t have to wait until the BFI runs another screwball season to watch a film I want to see.