I have been fascinated by the recently resolved standoff in the US TV industry between the second biggest cable provider in the country, Charter Communications, and one of the biggest TV providers, Disney.

Over the US Open tennis final at the weekend, and the start of the opening weekend of the new NFL season, millions of Charter cable subscribers in the US lost access to Disney’s package of channels.

Disney owns channels like ABC and ESPN, and this dispute came right in the middle of the US Open tennis, which ESPN has coverage of, college football getting underway on ABC and ESPN, and just ahead of the new NFL season, which again is carried by ESPN and ABC (in some weeks).

On Monday, all was restored at the last minute, and the key Monday Night Football NFL game between the Buffalo Bills and New York Jets was shown on ESPN (and ABC) to all Charter subscribers. However, it did go down to the wire.

That tends to be the nature of these disputes, and the new NFL season is often used by both parties to try to gain the best they possibly can from the deal. That includes pulling services from cable operators and both sides making public statements claiming the other party is the reason why they’re losing services. There’s an argument over fees, and they usually get resolved reasonably quickly, but not before annoying millions of consumers.

In the meantime, while the blockage was still on, US Open finalist Daniil Medvedev told reporters that he had to find a pirate feed of the action from his hotel when ESPN’s coverage via Charter was pulled. Disney did at least rush to provide US Open players with logins to a workaround feed so that they could at least see matches!

So far, so normal. The dispute is solved, and all is right with the world.

Except that this feels like it was different somehow. Charter’s claim was that while they pay Disney lots of cash for their channels, that money is not so much reinvested in the linear channels that serve Charter’s audience, but that it gets ploughed into the company’s streaming services, so that at some point in the future, the linear bundle is no longer a necessity for consumers – something that is already happening.

The cable companies are effectively patsys in the meantime.

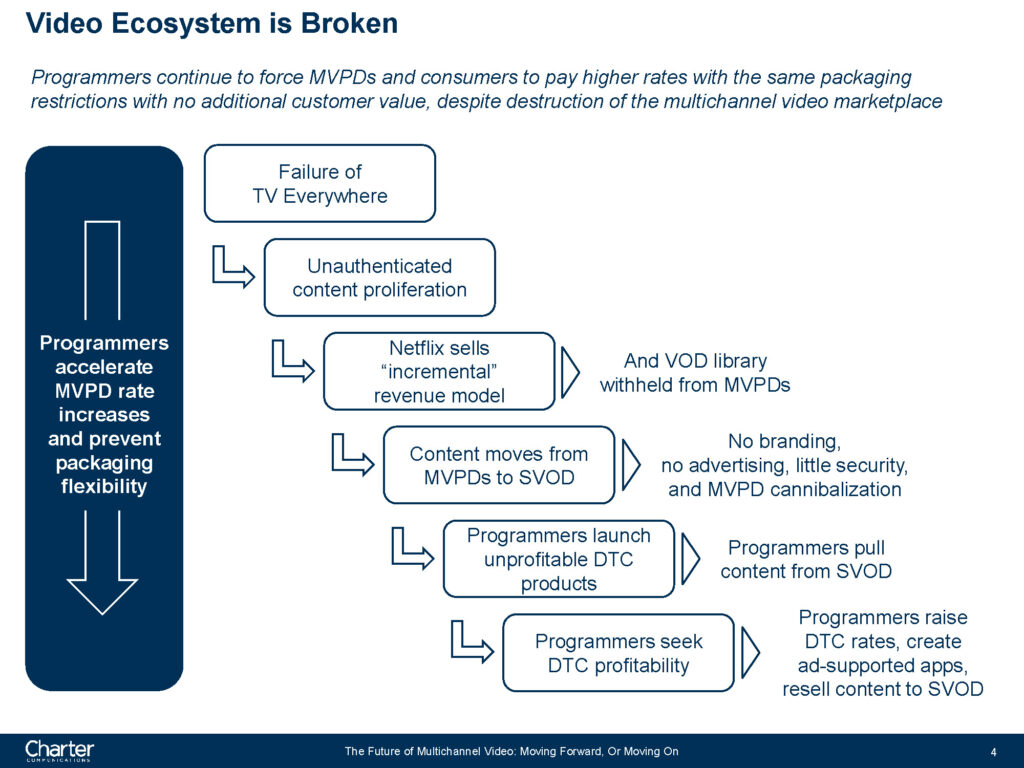

Charter laid out their issues in a document they published at the start of the dispute.

Breaking that slide down a bit:

- TV Everywhere was the idea that you use a single login, via your pay TV provider, to access services. The cable operators (Multichannel Video Programming Distributors or MVPDs) loved that because it was their subscription that provided the access.

- In turn that leads to programming accessed via other means. You don’t buy Netflix via your cable company, you buy it direct.

- Worse still from the cable operators’ perspective, Netflix has driven providers to move away from MVPDs and to their own subscription video on demand services (SVOD – e.g. Netflix, Paramount+).

- Those direct to consumer (DTC) services are not profitable at launch, so there are cuts to programming when the CFOs get their way.

- And to return to profitability, the programmers have to drive costs to consumers, all while adding ad-supported versions of thier apps and selling on their once exclusive programming to other suppliers.

“We’re on the edge of a precipice.”

— Chris Winfrey, Charter Communications CEO

And Charter probably isn’t wrong. Disney can see a declining cable world where it’s made big profits, and it has to move to a Disney+/Hulu/ESPN+ world. But those aren’t yet profitable, so something has to give. The claim is that Disney cuts investment in its profitable arms to shore up its new businesses.

US cable TV has for years been pretty lucrative. Getting precise figures is tricky because in the US, as elsewhere, you may pay the same supplier for your TV, broadband and phone line. But a consumer can easily pay $100 a month for a broad range of channels before paying for premium channels on top of that.

The chart below is based on data from 2020 but is indicative as to how some of those cable revenues are returned to the channel providers by the cable operators.

Source: WIZER (GETWIZER.COM); KAGAN, THE MEDIA RESEARCH GROUP OF S&P GLOBAL MARKET INTELLIGENCE, WIZER DATA FIELDED FOR VARIETY INTELLIGENCE PLATFORM BETWEEN SEPT. 28-OCT. 4, 2020 TO A SAMPLE OF 1,336 RESPONDENTS AGED 18-64 WITH A PAY TV SUBSCRIPTION

If you total those fees up, you get to $32.37. And of course, it’s not even as simple as this, because a supplier like Disney has a broad range of channels, not all of which are listed here. For the most part, you would expect Disney to only offer an entire package of its channels.

But the big thing here is that ESPN is by far the most lucrative channel in the cable bundle, earning vastly more than every other channel. And it is a bundle. Cable subscribers nearly all get ESPN whether they follow sport or not. Disney’s new agreement with Charter says that at least 95% of Charter homes have to have ESPN in the bundle. So the 70m or so cable homes are all paying nearly $8 (in 2020 anyway) a month for sport, regardless.

News Sidenote: Notice too how much more lucrative Fox News is compared with CNN? Both are must-haves for cable bundles, but in 2020 at least, Fox News was earning 70% more than CNN per cable subscriber.

And again, everyone is paying, regardless of whether they watch Fox News or not.

But it’s important to put that 70m number into perspective. Here’s a chart of the number of cable subscriptions in the US by year, since 2010 when it reached its peak at 105m.

Source: IBISWorld

Between 2022 and 2023, you can see the number fell by nearly 5m homes. That represents a rapidly increasing trend, as you can see if you look purely at the Year-on-Year changes in percentage terms over the same period.

Source: IBISWorld

Consider too that this period covers a pandemic when we were all spending much more time at home, and probably had more opportunity to watch TV.

Obviously the reasons for this rapid decline are largely the advent of streaming services. I strongly suspect that if you looked at the 70m or so homes that still have cable, they skew older.

One important note here is that these numbers are not just technically solely cable companies. MVPDs also include satellite subscribers to services like Dish, and also virtual MPVDs – services like YouTube TV and Hulu Live, which basically do the same kind of aggregation as legacy cable operators, but deliver them via the internet rather than a coaxial cable. And while they might offer so-called skinny bundles with not quite as many channels as a cable provider might offer, all the big channels are included, and the subscription fees are just as high as a result.

However, all this talk does largely overlook news, and especially sport. Because of deals with the cable companies who are paying so much for ESPN (and Fox News and CNN comparatively with most other channels), they want that programming exclusively. Yes, ESPN+ exists as a streaming offering, but it doesn’t include all the NBA and NFL games that air on the main linear ESPN channel. It’s much more about secondary sports that don’t air on the broadcast channel(s). Just as the short-lived CNN+ did not carry much in the way of regular CNN programming, that’s was because the agreements with the MVPDs require a certain level of exclusivity. ESPN and CNN are reasons to get cable. If you can buy them directly without cable, then cable dies, and the cable companies aren’t in a rush to hasten that.

At some point, that is going to have to change – cable is dying after all. And rapidly.

But the strength of the cable bundle is in its socialist nature. Everyone pays, and everyone shares the cost. If you sell everything directly, then not everyone pays. In a world where ESPN is sold outside the cable bundle, unless you can be sure that everyone currently subscribing via their bundle will pay the same amount outside the bundle, you’re going to have raise prices. At ESPN, they are definitely running the numbers, ad we can do some basic maths ourselves.

Based on 70m homes (probably too high) and a $7.64 a month cable fee (probably too low in 2023), we get to $6.4 billion a year! And that excludes advertising which is significant for a sports channel. It also excludes the separately accounted ESPN2 as well as other ESPN channels.

Let’s sense check that with Disney’s reported numbers. Disney doesn’t breakout ESPN from its overall cable offering, but according to The New York Times, the entire Disney cable networks division generated $14 billion in the first six months of fiscal 2023, with $3 billion in profit.

This also shows that while the revenues are big, there are big attendant costs to that programming, and for ESPN these are driven by sports rights. For example, in 2021 ESPN renewed its deal for Monday Night Football with the NFL for a reported $2.7 billion a season over a ten year period. The next big deal that ESPN has to negotiate is its NBA agreement which expires at the end of the 2024-2025 season. It’s currently worth $2.66 billion for the rights owned by both Disney and Warner Media Discovery, and with reports suggesting that the NBA is looking to double that number, everyone is going to have to dig deep.

But back to that putative $6.4 billion a year that ESPN is theoretically getting at the moment in cable fees. If it decided to go over-the-top and offer itself as a streaming service, what would it need to charge to maintain those same revenues.

Of course, if everyone who currently pays for a cable bundle handed over – rounding it out – $8 a month, then Disney is happy and consumers potentially are too (assuming their cable bills dropped accordingly).

But of course, a significant proportion of those older cable viewers don’t actually watch ESPN all that much. 70 million direct subscribers is a big target to get to; Netflix has 75.6m subscribers in the US and Canada, and they’re the most successful. They might not offer sport, but they do offer a wide range of programming from cheap reality to high end drama and movies. It seems unlikely that ESPN would get close to Netflix’s subscriber numbers with a pure sports offering.

If we generously assume that half the current subscriber base – 35m – take the service, what does ESPN have to charge to meet the same income levels? $15.28.

But even that percentage is probably too high. If only 25% of the current subscriber base takes up ESPN – 17.5m homes – that comes to $30.56 per month per subscriber.

And none of this factors marketing or churn. Cable customers tend to be locked in for long periods of time, and ESPN doesn’t really have to spend a lot to market their services separately since they’re part of the bundle (although to be clear, I’m sure ESPN has a very healthy marketing budget), so customers dropping out at the end of the NFL or NBA seasons aren’t as big a factor. With a month by month subscription it would be much easier to save cash between football seasons for example. And we’ve also not accounted for ESPN2 and other sub-channels.

So you can easily see $35 or even $40 being the amount needed by Disney from direct consumers just to stand still.

And all of this is before you consider sports rights. As mentioned above, the NBA wants to double its income, and that means channels will be competing potentially with deep-pocketed digital operators like Amazon or Apple, both of which have shown interest in sport.

In reality, we’ll go through a complex period of change. ESPN will be offered over the top for, say $35, while a declining number of people pay $8 via their cable bundle.

Perhaps Disney will do some bundling of its own. Disney already bundles Disney+, Hulu and ESPN+ in a variety of ways (with or without ads for Disney+ and Hulu at different price points), always incentivising the upsell. Adding in the full-fat ESPN and charging, say, $40 for the lot, as opposed to $35 for ESPN on its own is the kind of marketing approach that can work.

Sky Sports Sidenote: In the UK, we’re much more used to paying what a channel is worth. The same cable bundling never really took place here, and Sky Sports was always a premium upsell alongside their Sky Movies package. The current add-on price for Sky Sports is between £25-27 a month depending on whether you lock-in for 18 months. That’s about $34. TNT Sport is as much as £30 a month. Either way, the cost of the channel is supported by those who choose to buy a sports package.

That all said, every time a new Premier League rights package comes around, some ask why the Premier League don’t sell a “Premier League+” package direct to consumers and cut out Sky, TNT and Amazon. The truth is that they’d have to find 5m UK households each paying ~£30 a month all year around (including the off-season) to get the same amount. And that excludes production costs, marketing, churn and so on. All the risk would be on the Premier League.

Reports suggest that in this dispute, Disney probably caved. They cut the number of channels that Charter was required to offer – gone are services like Freeform, Baby TV and Disney Junior, all of which Disney will no longer be able to charge for. Charter wanted to be able to bundle some of Disney’s streaming products, and now different tiers of subscribers will get inclusive access to the “with-ads” versions of Disney+ and ESPN+. In return, Charter will market Disney’s DTC services to its broadband only customers.

In the medium term, the cable companies know that their customer base is heading towards zero for a television product. How long that takes is unclear, but it’s perhaps going to happen faster than we might think. The upside for them at least is that cable companies in the US essentially have local monopolies for selling broadband (satellite and wireless internet notwithstanding), meaning that Americans can continue to pay significantly more for broadband than we do in Europe.

But exactly how many channels consumers will pay for seems unclear. It’s not going to be as many. And a lot of current business models really aren’t going to work.