The most recent episode of the new(ish) podcast Search Engine with PJ Vogt asked the simple question, “Why is it so hard to figure out how many people watched Stranger Things?”

The question was posed by actor Maya Hawke who appears on the Netflix show. And it opened up an in-depth discussion about audience measure and in particular, the history of Neilsen, the company that is primarily known for its measurement of US TV ratings. The episode also examined the reasons that ratings exist (primarily for advertisers), and why ratings don’t really exist in the streaming world.

The latter reasons are complex and evolving.

At first, it didn’t really matter. Streamers like Netflix paid producers as though the show was a modest success, regardless of whether it actually was. In other words, if you sold a show to a network you might be paid $x, but if you sold the same show with the same budget to Netflix, they might pay $x + 20%. They paid more upfront, but as a producer, you’d be signing away other possible revenues that might be get down the line, such as being able to take the show to syndication, or selling it to others internationally.

That has all lead to a new world where the existing TV industry is rapidly falling away and streaming has become the new normal. There’s an understanding that unlike the old days, when those involved might often be able to negotiate higher payments if they were working on a hit show, this is unlikely to happen with the new model. So whereas once, the cast of Friends managed to negotiate a $1m an episode pay deal in 2002 in large part because everyone knew that the show was a massive smash hit with nearly 25m viewers a week, that no longer happens. In part because audiences are dispersed, and aside from big live sports events, nothing is getting 25m viewers at the same time.

In any case, today Netflix and their peers in the industry don’t provide that kind of detailed information available. They release a few datecdotes as they’ve been named (by the Entertainment Strategy Guy). These are numbers that sound number-y but don’t tell you an awful lot because they exist in isolation from comparable numbers from the same or other vendors. “More people trialled this series in the first 10 days than any other international series in the North American marketplace…” It sounds good but is essentially impossible to verify or make any comparisons.

Also in the last few days there was a discussion on the Pilot TV podcast about why people watch the soaps. I think it was genuinely asked, and it was well answered, because here’s the thing: in the UK the soaps are significantly more popular than anything from a streaming service. Indeed, it’s not just the soaps – it’s quite a lot of traditional television coming from the big public service broadcasters.

That might not be the impression that’s out there, as there are always buzzy new shows with big name stars and budgets many in the UK TV sector would die for. But significantly fewer people watch these shows.

We essentially know this because back in November 2022, the UK’s rating measurement body, BARB, announced that it would now be measuring Netflix, Prime Video and Disney+, the biggest three streamers in the UK.

To be clear, that does not mean that all and sundry can see how many people watched Wilderness on Prime Video this week, because BARB only makes a limited amount of data available publicly. So unless a programme shows up in BARB’s weekly Top 50 report, the data is invisible beyond paid-for BARB subscribers (and I believe there may be limits on what even they can do with that data).

In a world where TV never really stops being made available, with shows still able to be watched weeks, months or even years later on platforms like iPlayer and ITVX, the Top 50 report presents consolidated viewing data over 7 days. In other words, it captures live viewing (on linear channels), as well as any catch-up viewing over the next week.

I should note that while it does include mobile viewing, this is excluded for the three streaming services mentioned above. This does mean that if vast numbers of people are watching a Netflix show on their mobile, then that’s not being measured here. But according to reports, the majority of viewing to something like Netflix is on a TV set.

But with that in mind, how come when I run the most recent report (4-10 September 2023 at time of writing), all the shows are from BBC1, ITV1, Channel 4 and Channel 5?

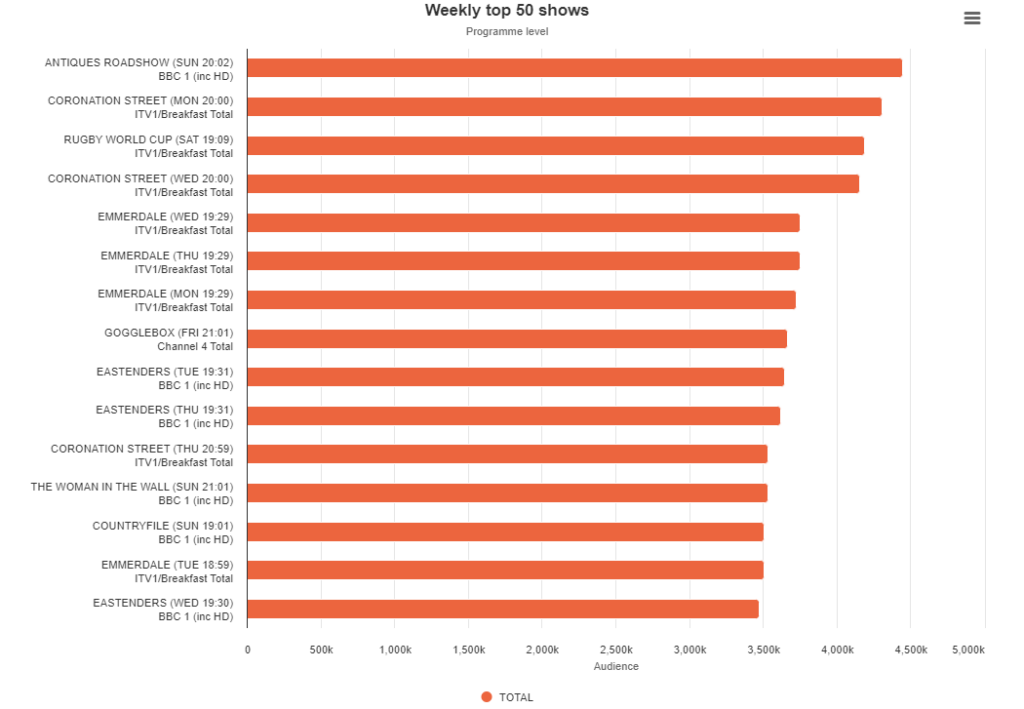

Here’s the Top 10, with Antiques Roadshow sitting at the top of the tree with 4.4m viewers. You’ll also note that the soaps do well as does the first England game in the Rugby World Cup on ITV1 and Gogglebox on Channel 4.

If you scroll through the full list, the #50 show is the ITV Evening News on Wednesday of that week with 2.3m viewers.

That implies that no show from Netflix, Prime Video or Disney+ achieved more than 2.3m in a single week (again, excluding views on mobile).

Indeed, it turns out that since November 2022 when BARB started reporting these numbers, very few shows from the streamers have cracked the list. In the week of 14-20 August 2023, At Home with the Furys (S1E1) made the list with 2.6m viewers coming in at #36 in the Top 50.

I suspect that this has been something of a hit in the UK – although perhaps less so globally. Netflix has a site that presents its Top 10 shows – separately for TV and Films. And for that same week, Netflix had the show as their #1.

And it has subsequently spent four weeks in Netflix’s Top 10, at time of writing sitting at #5.

If you go back to 19-25 June, Mathilda the Musical also made the list reaching #36 in that week with 2.6m viewers. And back at 6-12 March, Luther: The Fallen Sun reached #46 with 3.0m viewers that week.

To my knowledge, no Amazon Prime Video or Disney+ show has broken onto the list yet. The upcoming final season of Sex Education might be one to watch.

The one thing I would note is that viewership is only counted during that first week. So if many more people discover the show in its second week of availability, they’re not included.

So this isn’t to say that vast numbers of streamers’ shows are unsuccessful. They’re just not nearly as big as we sometimes might think they are, although obviously the streamers are seeking global audiences, not just UK ones.

Two of my favourite shows ended this year. Succession and Happy Valley. The former aired on Sky Atlantic, and had acres of press coverage, spin-off podcasts, interviews with the stars and much more.

It didn’t get into the Top 50 the week it aired in the UK. Instead, the list that week was dominated by Britain’s Got Talent, the soaps, and British dramas like The Steeltown Murders and Ten Pound Poms. Roughly 1.3m watched the final episode of Succession in the week it aired (And again, that cumulative audience will grow over time).

On the other hand, 10.6m watched the final episode of Happy Valley in the week it aired. Another culturally important moment. But because it went out on BBC1, it was a vastly bigger show that Succession, or anything Netflix has.

What will be interesting to see is how much data gets made available over time, because many of the streamers now have lower-priced subscription tiers that come with advertising. And as we have seen above, advertisers tend to require data to support their expenditure. Whether that will lead to a full third-party independently audited system of measurement (as I suspect BARB is trying to become), or whether advertisers will allow platforms to “mark their own homework” when reporting data, only time will tell.

And it should be said that one of the key issues surrounding the ongoing writers’ and actors’ strikes in the US is around data. Producers essentially don’t know if their show is a hit – or at least how big a hit it actually is.

Third party companies like Neilsen in the US, or BARB in the UK, can provide level of measurement, but it’s limited. In a world where there was a finite number of TV channels, measuring them to a satisfactory level was a statistical sampling exercise. How many thousands of homes do I need to put smart meters in to measure TV consumption accurately enough that it’s representative of all viewing? In the UK, for example, the BARB panel is being expanded to 7,000 homes. But if you’re trying to measure consumption of potentially tens of thousands of series, many of which are always available, then you have to scale up your sample a lot to have statistically significant audience measurement for all of those shows.

The other way to do it is to get the consumption data direct from the streamers themselves. This was never an option in the broadcast TV world, because you literally sent the signal out to the world from a big tower, and weren’t able to tell whether one person or one million people were watching. Netflix, on the other hand, knows exactly how many accounts are watching any show at any given point.

But in the meantime, when the next season of Loki drops on Disney+ and lots of people excitedly talk about how everyone is watching it, just consider that vastly more people are probably watching The Antiques Roadshow on Sunday nights on BBC1!