Podcast listening metrics have long been seen as something as a bone of contention. In the digital advertising world, they’re seen as inferior to metrics delivered by other parts of the industry, because while you can be pretty sure a podcast advert has been delivered, you can’t be sure that it has been heard.

As a consequence, the emerging podcast sector, especially in the US, has had to battle the advertising industry to gain full acceptance. This has meant that a large majority of current podcast advertising is led by direct response advertisers i.e. coupon or offer codes when you sign up to buy a product or use a service.

Advertisers are happy to go along this route because they can easily track how successful a particular campaign has been on the basis of sales made using the various coupon codes.

That’s great as far as it goes, but it leaves a large chunk of the advertising market on the table. If you watch a TV break or listen to a commercial break on the radio, you won’t normally get quite as much direct response activity, particularly from national advertisers. Ford knows that you’re not going to buy a new car right now, and in any case, the price will be a negotiation between the customer and the dealer, and probably not subject to a 20% off coupon code! They just want you to consider a Ford the next time you buy a new car.

FMCG products (Fast Moving Consumer Goods such as washing powder or chocolate bars, and often referred to as CPG products in the US) make up a significant chunk of consumer advertising, but largely go unheard on podcasts because there’s no easy way for marketers to track whether an ad for a detergent placed on a podcast has been successful and shifted product.

That’s not to say that the success of traditional television advertising is easy to track either, and advertisers continue to happily spend billions on that medium. It’s not for nothing that the most famous quote in advertising is, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.”

Of course, ironically, while digital is supposed to be the ultimate targeting device, it turns out that P&G, one of the biggest FMCG advertisers on the planet, has decided that it has been attempting to target far too much on platforms like Facebook. That’s perhaps not surprising because, well, everyone needs to buy washing powder and toothpaste, so advertising widely would seem to make the best sense (see the Ad Contrarian for lots more on this).

And it’s not as though there aren’t other problems with advertising in the digital space including fraud and ad-blocking amongst others.

Anyway, the US podcast community is trying to gain more acceptance among the advertising community by working to ensure that everyone measures podcasts the same way, which is very sensible. While this might seem straightforward, in reality, counting podcast downloads is actually a case of interpreting server log files.

This week the IAB has released its Podcast Ad Metrics Guidelines, to both explain the challenges and to ensure that everyone counts podcasts the same way.

The document itself is fairly readable and it’s has a few interesting facts that are worth examining in more detail. It’s probably a first iteration of a living document, with a working group sitting behind it.

One interesting piece of information is the detail of how podcasts are consumed. Five groups on the working party submitted data about podcast platforms, and a table was published as a result, which I’ve reproduced below. Note that the data was based on April 2016.

| Platform requesting podcast file | Range of market share % |

|---|---|

| iOS – Apple Podcast App | 45-52% |

| iTunes | 8-13% |

| Browsers | 6-14% |

| Stitcher | 2-7% |

| Everything else | 12-30% |

NB. It’s not explicitly clear if these are US-only figures, or global numbers based on a number of firms based in the US. The partners are Podtrac, Blubrry/RawVoice, WideOrbit, Libsyn and PodcastOne, all of whom I believe are available globally to podcasters.

What I found especially interesting is that Apple isn’t quite as dominant as I’d previously thought. At least in terms of apps used to listen, with a cumulative 53-65% share of podcasts which is lower than the ~80% I had previously thought it might be.

That’s not to say that Apple isn’t vitally important in the transmission of podcasts. Many non-Apple apps use the iTunes Search API to populate their apps with a current list of podcasts. If you’re launching a new podcast, there are a lot places you want to list it. But first and foremost, it’s still the iTunes store if you’re trying to maximise audience reach.

The other interesting question is about downloads versus streams. The report goes into some detail about this, and of course different companies can do this differently. While “traditionally” an app has downloaded podcasts in the background for later playback, today apps allow you to “stream” directly as the podcast downloads.

Beyond that, there is in-browser listening where often a podcast player appears on a webpage and is played back from there. The chart above shows that as much as 16% of podcast plays are listened to this way. Depending on the technology being employed, an in-browser podcast player might be a proper streaming solution, or it might in fact be simply pulling an mp3 to a wraparound player. The user will not notice the difference.

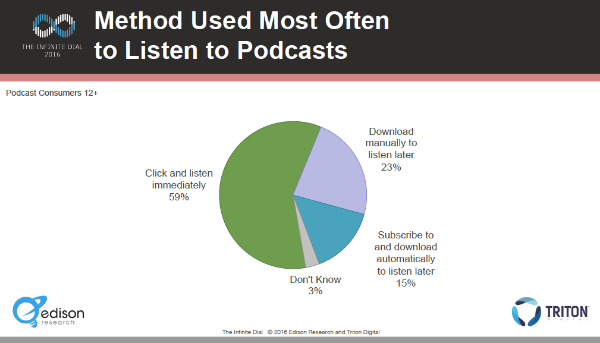

What’s interesting is how this compares with other research on podcast listening and the emergence of the “click and listen” model. A recent Edison Research/Triton Digital report showed 59% of podcast users saying they click and listen immediately, as opposed to just 15% saying they subscribe in the traditional manner.

These numbers seem to suggest that although people are actually mostly listening through traditional podcast platforms like podcast apps, they’re actually choosing to download and listen at the point of consumption. It’s for that reason that so many podcasts implore listeners to subscribe, because if you’re relying on click to listen, then it’s entirely likely that listeners will miss episodes of podcasts.

But I’d also love to dig deeper into the numbers in the chart above, because the opacity to the regular podcast listener of how podcasts actually work means they may not actually know what they’re doing or how the audio is getting to them.

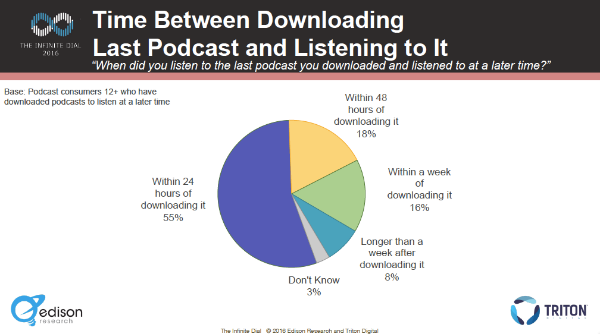

I say this because the chart above suggests that 38% of people either subscribe or manually download to listen later 42% of people say they listen to podcast two days or later after the podcast has downloaded. Add in a proportion of the large percentage of people who listen with 24 hours of a download, and you have a larger number of people listening via a download-and-listen-later method than say that’s what they do.

Separately, the podcast hosting company Blubrry has crunched the numbers of how its own podcasts are delivered as best it can.

Blubrry defines four different categories of distribution:

Mobile apps – which can both download and “stream” (i.e. download to listen instantly)

Desktop apps – mostly for downloads, and most likely iTunes (accounting for 80% of listening in this category)

Desktop browsers – where you can either “stream” from the page (in this instance an HTML wrapper around a hosted mp3 file, as opposed to a properly streamed file as the BBC often provides)

Mobile browsers and TV apps

Blubrry estimate that within the 71.6% of mobile apps consumption, 39% is accounted for by the iOS Podcast app. And half of that is streaming rather downloading. Whereas of the desktop browsers, two thirds is streaming, while a third is downloaded.

All in all, bespoke podcast applications, whether on mobile or desktop platforms, account for 85% of podcast listening.

Returning to the data in the IAB paper, what it also makes clear is that bespoke podcast apps – e.g. apps created for a particular podcast or podcasting company – are not very popular. The advantage to the podcasting companies is clear – they can properly track listenership and advertising consumption. But to the listener the benefits are less clear. It means one more app on your phone, and the app probably won’t let you listen to other podcasts.

All interesting detail about how people actually listen to podcasts.