Two data points:

- A Morgan Stanley note for investors is reported to claim that Spotify is now the #1 podcast platform beating Apple.

- MIDiA Research publishes a blog based on their regularly published tracking report that says “Spotify AND Apple Lead Podcasts – It’s All Down to How You Measure It.”

From these two reports – which are both proprietary, so not fully available publicly – you might begin to think that Spotify is now the key application for listening to podcasts in some markets. This has all led to some heated discussions, while causing others to question the perceived orthodoxy.

[Sidenote: A Twitter poll is of zero value. Don’t do one, and don’t rely on the results of one.]And if you’re a podcaster who looks at your own stats, you might be questioning whether this reflects trends that you are or are not seeing.

So what’s going on here?

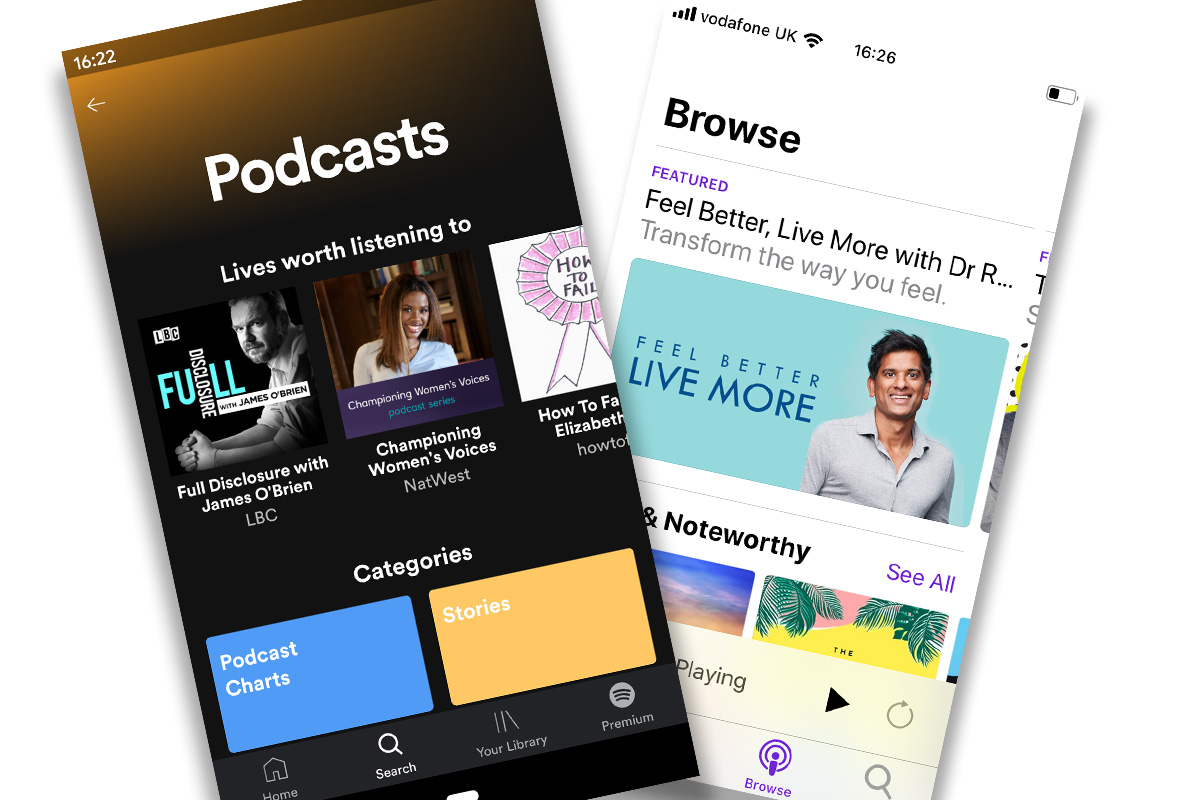

First of all, it seems very likely that Spotify has leapt up a lot in the last twelve months. During the last year they have placed increased emphasis on podcasts, presenting Music and Podcasts with equal prominence within Your Library in their app.

They obviously also went shopping for a number of podcast companies including Gimlet and Anchor. At the recent CES they announced the introduction of their own new advertising platform – Spotify Podcast Ads – which they claim offers more effective measurement (or tracking) than others. Indeed Spotify reportedly says that their users who stream podcasts listen to twice the music that non-podcasting listeners do.

Set against all of this are the stats that podcasters are likely to be seeing based on their own feeds. Most podcast hosts provide metrics which include some kind of breakdown about which apps are being used to listen to a particular podcast feed.

The group who tends to report podcast app consumption via User Agents most openly and regularly are Libsyn, the podcast hosting company. Their in-house podcast, The Feed, regularly reports stats based on User Agents, last reporting numbers in November. In episode 156 of The Feed, they reported the following shares based on downloads. The discussion is just after 55 minutes in, and they report the following:

Apple Podcasts/iTunes – 58%

Spotify – 13%

Overcast – 2.4%

Stitcher – 2.4%

Castbox – 2.15%

Google Podcasts – 1.9%

Podcast Addict – 1.7%

Pocket Casts – 1.3%

Others had less than 1%. But 4% of listening was accounted for by apps that don’t present a User Agent (i.e. we don’t know who they are).

[17 September: See Update #2 below for December 2019 figures which Rob Walch at Libsyn shared with Podcast Business Journal. Spoiler: They tell a very similar story to the numbers above.]Libsyn would seem to be a fair reflection of the podcast market, with a significant number of podcasts hosted by them. But arguably they’re aimed at smaller producers, with bigger groups and networks having hosting providers they’ve either built themselves or outsourced to major third-party groups who offer advertising solutions. So there is an argument that listening to a series from a major publisher might be at variance with these.

But I should reiterate that every set of stats I’ve seen would tend to back up those from Libsysn (and I am privy to some big ones). Apple remains the biggest player, although it’s share is falling. Spotify is emerging as the clear number two (although not necessarily across every genre – Libsyn notes that tech podcasts under-perform on the platform), and everybody else some way behind.

And obviously, Spotify might well promote some podcasts – most apps have some kind of promotional or discovery element built in – meaning that listening to a particular podcast series might be skewed in favour of one podcast app or another.

So how do you get from Apple at 58% and Spotify at 13% to a position where Spotify is reportedly equal to or bigger than Apple? What’s happening?

Well, as with anything, it really depends what you’re measuring.

If we step away from podcasts for a moment, and look at radio, there are two key measures for any station (the same is true of TV incidentally) – reach and hours (or share in commercial parlance).

Reach is the number of different people you’ve reached. This is the number you’re likeliest to hear most about. When a radio audience is being talked about, the number of people who heard it is what reporters mention.

Hours is the amount of time spent listening to the station. It’s actually much more important to advertisers, because the longer you spend listening, the more opportunities you have to hear an advert. Share is essentially this same figure expressed as a percentage of all listening. With either measure, you want as big a number as possible.

Returning to podcasts, the stats that most people talk about are downloads (and streams, as we move into a world where we have free/cheap internet available at all times). While this isn’t quite analogous to hours or share, it’s close – particularly to share. If every podcast were of equivalent length, then it would be a direct proxy for share. If I download one podcast then I count as one. If I download five podcasts, I count as five.

Most podcasters only really have access to this number. We know how many downloads we get, and if it’s 1,000 this episode, and 1,000 next episode, then it’s probably the same 1,000 or so people hearing both. But we don’t absolutely know that. Only systems that have sign-ins and unique identifiers (like Spotify) can deliver this with certainty, and even then, if the podcast is available beyond that platform, even they can’t provide an overall reach figure with accuracy.

Which brings us back to the reported numbers at the top of this blog post.

First off, they’re both surveys. That is, they’ve taken a sample of populations and asked them questions about their recalled behaviour. The samples in both instances seem decent – Morgan Stanley sampled around 2,000 US residents; MIDIA sampled around 4,000 residents across several territories. The results should be robust with those kinds of sample sizes, but they are samples and not actual figures that the likes of Libysn is reporting.

But the key thing is the question that was asked.

While neither has published openly their respective questionnaires or full tables of results (they may be available for subscribers) [16 Jan: See update below for a link to the details of the question MIDiA asked], it would seem that they’ve asked survey respondents which platforms they use for listening to podcasts.

What that means is that someone who listens to just one podcast on Spotify is of equal importance to someone who listens to 100 podcasts on Apple Podcasts. In radio terms, they both represent a reach of one.

The danger, then, is overstating the use of Spotify for actually listening to podcasts.

Because if download stats are saying one thing, and a podcast survey is saying something very different, that’s really the only assumption we can make if the data is to be trusted.

What seems undeniable is that Spotify has grown its share of podcasting, and quite probably the overall volume of podcasting, fairly substantially in the last year.

I think it’s also reasonable to hypothesise that Spotify has introduced new people to podcasting, but that these people are more likely to be listening to fewer podcasts than people on other podcast-specific platforms, who are more likely to have been listening longer.

Fundamentally, you probably install the Spotify app for music. Podcast listening is a bonus or addition for most users. But if you open Apple Podcasts, you’re opening it to do one thing – listen to podcasts.

Other things to consider:

- There are people who neither own an iPhone, nor have a Spotify account – quite a lot of them. So while Apple and Spotify are the leading two apps, if you only concentrate on them, you’re ignoring a large number of people.

- The situation can be very different in different markets. Most surveys only consider the US – where Apple tends to have a higher market share. Even broader surveys only consider a relative handful of European or English-speaking territories. So making bold statements off the back of these surveys can be very misleading.

- Recall surveys are challenging to conduct and favour more established and familiar names. These surveys are not based on actual usage, but what people say they’re using. What people say, and what they do might not be the same thing.

Apple’s share of podcasting should continue to fall. In a perfect world, it would directly reflect Apple’s device usage market share at best Some Apple users might prefer Spotify or another podcatcher after all.

But that’s not currently the case in terms of all download stats I’ve seen. So you would expect that Spotify and others should continue to make inroads into the market in both usage terms, and share of downloads or streams.

However, the data needs to be interpreted properly, and care needs to be taken to explain what research is actually inferring.

There is significant growth in podcasting still to come – more people don’t listen podcasts than do listen. Growth has not been as fast in some non-English markets. And some parts of the world still remain far behind the West and parts of Asia in terms of internet accessibility full stop.

Just be a little wary when someone reports something extraordinary. Our digital usage is evolving all the time, but radical shifts over very short periods are quite rare.

[UPDATE – 16 January]

MIDiA have posted an update on their website detailing their report’s methodology some more.

The first thing I’d note is that the sample drops to below 600 across the four measured territories once you consider only podcast users.

They show that the question is based on a pre-populated list that includes some country-specific apps like BBC Sounds in the UK. I’m not entirely sure that the right selection is there – there’s no Castbox for example, while an app like Luminary which is included, is still very small in comparison to most of the others.

They counter some of the criticisms about things like listening to podcasts via Apple Music (which you can’t really do), because they claim that some podcasts are still to be found in the Apple Music ecosystem. I’m not sure about that.

They also note that Google Podcasts performs surprisingly well and suggest that this might be down to large numbers of relatively inactive users. While it’s true that Google has upped its podcast game and has presented play buttons in search results in recent months pushing users to their app, I’d question whether or not that is more to do with brand awareness than anything else.

Finally, presenting both Apple Podcasts and Apple Music might mean that some people tick the wrong box – you’re far likelier to be listening to podcasts on Apple Podcasts, but it’d be easy to tick Apple Music instead when you’re completing the survey. (In point of fact, quite a number of podcasts are still listened to via desktop, and this survey doesn’t really capture any of that listening).

[Update #2: 17 January]

As noted in today’s Podnews newslettter, Rob Walch of Libsysn has shared their download/stream percentages for December 2019. They tell a very similar story to the numbers above.

Apple Podcasts and iTunes – 59.6%

Spotify – 11.6%

Stitcher – 2.50%

Overcast – 2.40%

CastBox – 2.15%

Podcast Addict – 1.94%

Google Podcasts – 1.90%

Pocket Casts – 1.30%

As before, the remainder have either less than 1% share, or did not set their user agent to provide app details.

See the Podcast Business Journal Piece for the full list and numbers.

Note that the story talks about “setting the record straight”, although as I’ve explained in this piece, and as Podnews points out today, the MIDiA research (and probably Morgan Stanley too) are looking at a different measure.

[Update #3: 22 January]Via Podnews, Chartable has released detailed data comparing unique devices with share of downloads, and it makes for interesting reading.

Using a sample of 200m downloads in January 2020, they identified 40m unique devices. These show that, as hypothesised, Apple has a bigger share of unique downloads, but a smaller share of devices. However, Chartable’s data still shows Apple’s device share as being bigger than Spotify’s. And as Podnews notes, the numbers that Chartable presents are very close to those of Libsyn.

Chartable notes that Apple Podcasts downloads podcasts you listen to in advance for you by default. Obviously that doesn’t guarantee a listen. Spotify, on the otherhand, only downloads on request. But Apple Podcasts does stop downloading if you don’t listen to a podcast. So if you subscribe to The Daily but don’t listen, it stops downloading.

The other thing to note is that the number of unique devices is a proxy for, but not the same as “reach” as defined above. If you listen to podcasts on your iPhone, your iPad and your Echo you’re probably counted as being on three unique devices which isn’t the same as “reach” which should be just one person. But behaviourally, we know most podcasts are listened to on phones, so this shouldn’t have a massive impact.

Finally, Libsyn combines Apple Podcasts and iTunes, whereas Chartable looks to have broken them out. So the comparison with Libsyn’s data isn’t quite the same.

Hopefully, I can now park this subject!