This entry is also available as an episode of Explore from The Cycling Podcast much of which I recorded at this year’s Étape. Listen to the episode below. Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts!

In October each year, ASO, the organisers of the Tour de France and now the Tour de France Femmes, announce the route of the race for the following year. Alongside the professionals who will carefully look over the parcours of the upcoming stages, thousands of amateurs are also interested in the announcement, because one of those stage will become the route for the following year’s Étape.

ASO last week announced that the 2024 route will be from Nice to Col de la Couillole, covering 139km and 4,600m of climbing. This will also be the penultimate stage of next year’s Tour which finishes in Nice to avoid Paris ahead of the Olympics.

The Étape – or Étape du Tour – is one of the harder one-day cycling Sportives an amateur can do. It’s scale means that a lot of people are able to participate and because it’s run by ASO, and so it carries with it the sheen of the Tour de France.

The stage chosen each year is often one of the harder mountain stages of the three-week men’s professional race. It will invariably mean climbing thousands of metres of altitude over a distance of well over 130km. Those climbs tend to include a least one or two of the Tour’s famed mountain summits, and it’s that climbing that really makes things difficult.

There are other sportives which are tougher – The Tour du Mont Blanc is 300km and climbs more than 8000m; the Maratona Des Dolomites is also hard topping 4000m; and La Marmotte is also usually run over more than 5,000m.

But the Étape is the most popular, now with a cap of around 16,000 competitors.

In 2023, the Étape replicated the route of Stage 14 of the mens’ Tour, being 157km in length and climbing 4,100m of altitude over five designated Cols from Annemasse just outside Geneva near the Franco/Swiss border to the ski resort town of Morzine sitting amidst the Alps.

The Tour de France organisers categorise climbs as being from Cat 4 (the lowest, and therefore “easiest”) through to Cat 1 (the hardest). Then there is a special category of climbs that are even harder – Haute Categorie or HC. These are the very hardest climbs.

There are two key numbers to look at with climbs – the length of the climb, with the longer climbs tending to be harder, and the gradient of the climb. Anything below 3-4% isn’t really even counted as a climb, although your legs will tell you otherwise.

The first climb for this year’s stage was to be the Col de Saxel and was considered only a Cat 3 climb, being 4.3km in length and with an average gradient of 4.6%. On the face of it, an easy climb to warm up with, although it comes off the back of another “uncategorised” climb that isn’t counted by the organisers. In truth, you will have been climbing for around 10km by the time you reach the top. But the climb comes early on when everyone is fresh.

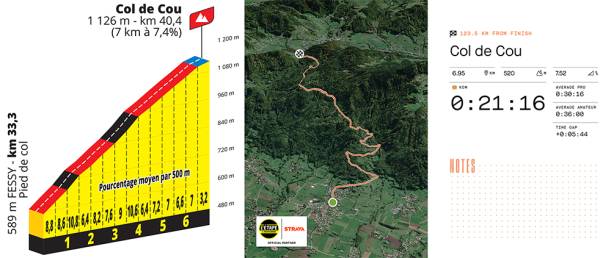

Then we move onto Col du Cou, which is a Cat 1 climb with a 7km length and an average gradient of 7.4%. That average does hide a few steeper ramps in the middle of it, and the top is flat, so it averages out that way.

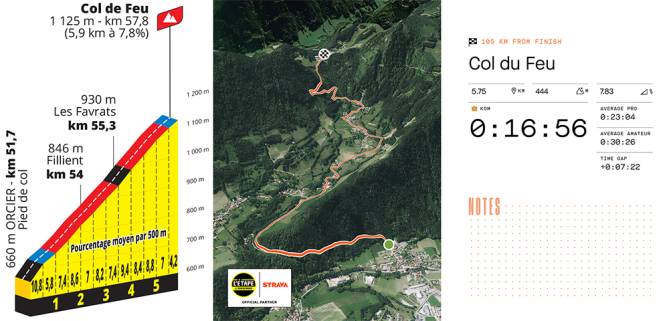

Next up is the 5.9km Col de Feu, which might be short, but has a gradient of 7.8% on average and begins with a first kilometre averaging over 10% in gradient.

Then there are the final two really hard climbs.

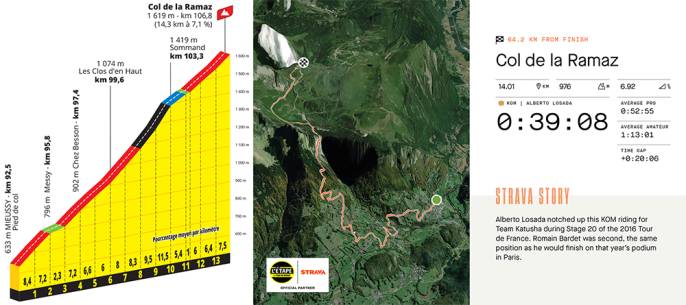

The Col de la Ramaz is first up at 14.3km in length with a gradient of 7.1%. That means it’s quite wearing. And again, the stats can be deceiving. There are a couple of flat-ish sections first early on, and then later. That means that in the middle, there are steeper ramps with gradients that stray into double digits with the tenth kilometre average 11.5% for the entirety of it!

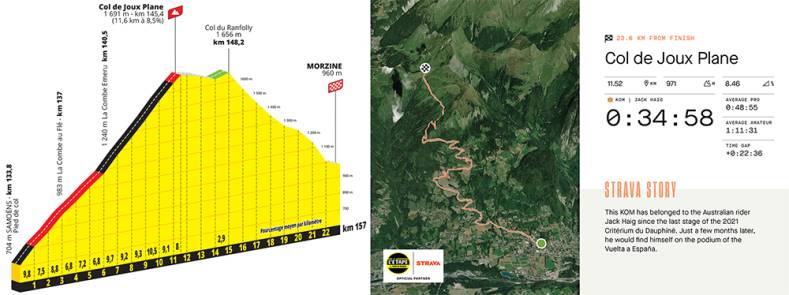

Finally there’s the Col de Joux Plane which is 11.6km at an average gradient of 8.5%. Again, the average hides some unpleasant stretches. The first kilometre is at 9.8%, and from 6km to go until the end, the gradient is never less than 9%! Averages are funny old things.

I’d long wanted to complete an edition of the Étape, and when I achieved that goal last year, I was overjoyed. And I immediately decided that I needed to do it again. So, I again signed up with Sports Tours International, a company who specialise in the logistics surrounding these kind of events, and booked up for the 2023 edition.

But in the leadup to the event, I wasn’t 100% certain that I was at the same level of fitness that I’d been in 2022.

I’d put back on a few kilos that I’d previously lost, and hadn’t been doing quite as much virtual mountain climbing as I’d done the previous year. Living in the southeast of England, we don’t have too many long and sustained climbs, so riding up virtual mountains is a much more achievable goal.

That all said, I had been doing a lot of outdoor cycling in general, and was well on track to exceed 10,000km for the year (Something I would manage by early October).

I did do a Functional Threshold Power (FTP) Test a few weeks before heading to France, and that showed that my power level was at a new high – 352W. Meanwhile, I did a 200km ride that took in over 3,000m in climbs. That showed me that I could sustain the effort required to get over the 4,200m I would need to ascend at the Étape.

In 2022, I’d gone out to France early to “get my legs in” ahead of the event, and this year I decided to do the same thing. With the event taking place on a Sunday, it’s perfectly possible to make it a long-weekend – flying out on a Friday and returning on a Monday to minimise time off work as well as the cost and expense of travel.

But that would significantly limit any kind of “acclimatisation.” I’d found previously that having time to do some long, real-world climbs in advance, had readied me properly.

So, I did the same thing I’d done in 2022 and went early. I booked some extra nights in the same Annamasse hotel that I would staying in over the weekend of the event – a budget French chain hotel. Then I flew out to Geneva the Monday before, taking the train from the station into Geneva from the airport, before changing to a local train for the journey out to Annamasse.

Annamasse sits just across the Swiss/French border from Geneva, which is very much on the Swiss side. It’s not quite an urban suburb of Geneva because there are fields and farmland beyond the two, but it’s clear that many of residents on this small French town, commute into their nearby Swiss city for their day jobs.

(It’s worth noting that although there are no check- or stop-points at any of the numerous crossing points between the two countries, there are clear differences, and you will be spending Swiss Francs and not Euros in Switzerland. Even your Euro charger may not quite work in Switzerland as I later found to my cost at the airport.)

This was the first time I’d flown with my current bike, and I’d invested in a bike bag to carry on the plane. This was a whole new world for me. My previous bike bag was a very inexpensive model that I’d bought years earlier on Amazon, primarily because I’d planned a rail trip with my bike. On booking train tickets, I had found that for one leg, I couldn’t get my bike on the train because it was full. I’d circumvented this issue by buying the cheapest bike bag I could and carrying my bike as “luggage” on the leg where I’d not been able to get a fully assembled bike carried. The guard had looked at me very suspiciously at the time, aware that I was trying to skirt the rail company’s rules. But my theory was that I’d similarly be able to carry a double bass onto the train if I’d wanted to (Double bassists may dispute this claim). I then posted my soft bike bag home when I reached my destination!

That bike bag wasn’t sufficient for a plane, and ideally, I’d get hold of a hard-shell case. These are made of solid materials that theoretically protect bikes much better than soft-shell cases. The primary issue with them is that they don’t pack down. So, you either hire one for the time you need it, or you live somewhere with a large garage/outhouse where you can keep the box when you’re not using it.

Hiring a hard-shell was a possibility for me, but once you’d allowed for the rental fee, and either delivery or collection challenges (I don’t own a car), the costs would begin to mount up. A soft-shell case might not be quite as robust, but it could pack down afterwards, and would at least fit through my loft-hatch for storage.

Incidentally, researching such things is very hard, as everyone has a good – and a bad story about every model. In the end, I went to eBay to bid for a Scicon Aerocomfort 3. The first one I found which had been used once, and I got “sniped” on it at the last second. Then I found a poorly described “Used” condition one from the account that resells Wiggle returns. I took a plunge on that, and got a battered box, containing a brand new and completely unused model, for a price significantly cheaper than I could have found it anywhere else. I assume the previous buyer returned it unwanted, and whoever listed it on eBay didn’t accurately explain how good the condition was. I’m happy because I now have a bag ready to go whenever I choose to travel somewhere else with my bike.

Packing my bike did see me go full “belt and braces” by adding some pipe lagging to forks and stays in various places, and the purchase of an Apple Airtag was something else that seemed sensible. That way at least, if the bike didn’t make it at either end, I could see where it had got to.

In the end, that does add a certain amount of additional stress because in my case I found myself sitting in my seat on the plane anxiously hitting refresh on the Apple Find My app, because it was telling me that my bag had last been spotted 13 minutes ago somewhere on the other side of the airport!

I can report however, that my bike made it intact in both directions.

Checking in at Luton Airport for my flight out had been another thing altogether. With a 7:30 am flight, Easyjet told me that baggage checks would open at 5:30am. I arrived a little before then thinking I’d swan through security and grab some breakfast before my flight time. Instead, I was faced with a queue that filled the entire departure hall. It seemed as though all of Easyjet’s flights took off within minutes of one another, and because it was July, like me, everyone had hold baggage for their trips.

I needed to first of all queue to get my baggage weighed, before taking my bike bag to the oversize counter where someone else would process it. But I had to get into both queues. Suddenly I was looking in fear at my watch. Time was marching on.

Once I’d finally checked in the bike, I rushed to security where, you guessed it, there was another enormous queue. It was moving but not as fast as I’d have liked, snaking backwards and forwards. At several points I was going to try to queue jump to ensure I got to the gate before it closed, but I just about managed to clear security. My gate was now displaying “Last Call” and I sprinted through the airport from security to the gate without stopping to make it just in time to the flight. All the running I’ve been doing recently proved useful!

At the other end, things were much easier. I wheeled my bike out of Geneva airport, got a train into the city centre and then another back out to Annemasse. From there, I wheeled my bike to my hotel.

On reassembling my bike, I did run into a brief problem. I’d planned to go for an early spin, but my electronic gears were giving me problems. I’d charged the battery before coming, and I’d brought my charging cable with me, but things were just not working. I was beginning to panic and had convinced myself that the battery was flat and my charging cable no longer worked. I found that there was a bike shop not too far away. But they were at a loss to help and couldn’t sell me a cable. I found a larger bike shop a little further away (Annemasse is well equipped), and there a mechanic found that there was nothing wrong at all. He showed that my cable was now working, and sent me on my way smiling.

Before heading out to France, I dropped a note to Lizzy Banks, rider for EF Education–Tibco–SVB, and presenter on The Cycling Podcast. She lives not too far from where I was staying, and she furnished me with a few routes that would hopefully not wear me out too much, but test the legs.

So it was on Tuesday morning, I headed south on a 94km circuit that took me first to the small town of Thorens Glières, before beginning the proper climb of the day up to the Plateau des Glières. The climb had some fantastic switchbacks, but on the top the views were amazing.

You could understand why French Resistance fighters chose this as a location to defend themselves against the Nazis during the Occupation in WWII.

There was a section of gravel before the descent began. I passed plenty of other people coming up the other side which to my eyes looked harder. But either way, my stats told me I’d climbed about 1900m throughout the day, with the Plateau itself peaking at just over 1400m.

The following day, I followed another route suggested by Lizzy, and rode the Circuit du Salève. You head south-west from Annemasse and basically skirt around the bottom of a mountain range. At the southern end of the range is the small town of Cruseilles where Lizzy had suggested that I should visit the boulangerie which did indeed have a fantastic array of cakes to help power me on for the proper climb of the day.

There are two summits at the top of Salève, before a twisty fast descent takes you back down to the edge of Annemasse. A much more modest 62km and 1300m of climbing day.

Not wanting to burn myself out too much, Thursday’s ride was much flatter, with only 500m of climbing. I cycled a route which looped around the outskirts of Geneva before hugging the southern end of the lake and returning to the start.

This was a low impact day, but the weather was nice, and the roads were nicer. The route kept to small village roads and some gorgeous cycleways. At one point I saw signs for CERN, the European Organisation for Nuclear Research and home of the famed Large Hadron Collider. When I examined the map more closely later, I realised that I must have ridden over the 27km underground ring a couple of times during my ride.

In the afternoon I caught the train back to Geneva to look around, and noticed that the officious Swiss police were very actively fining any cyclists who dared to ride their bike through a pedestrian area. To be fair, there were clear “No Cycling” signs, but elderly and young alike were being fined, with portable payment machines taking the penalties there and then!

Now just a couple of days away from the event itself, and the Étape “village” was opening today. Essentially a series of stands populated by cycling companies, it is the place where you collect your “bib” – your race number, and various other bits and pieces you need for the event.

But before I headed out there, I was going to get one more Lizzy Banks suggested ride in. The ride to the Col de Saxel would replicate some of the early part of the route (although the roads I rode were slightly quieter than the main roads that would be closed for the event). I reached the village of Saxel and where the Étape would continue onwards I turned off and up the mountain to the monastery (in fact there are a couple) high over the valley.

It’s a lovely climb and because it’s a dead end at the top, the only traffic you encounter are people coming to walk in the woods. From the top there were fine views right over the Alps towards Mont Blanc.

I rolled back to Annamasse a different route, and headed out to the Village for my bib collection. I had thought that I might be able to watch that day’s stage of the actual Tour de France on a big screen there, and they would certainly be showing it. But it was very hot, and there really wasn’t enough to keep me hanging around.

I watched that day’s stage back at my hotel.

The Saturday before the Étape and Annemasse was filling with cyclists. Still more would be gathering in Morzine which, since it’s a major ski resort, can accommodate the thousands of visitors a bit more easily.

Tempted though I was to go for a ride, I knew that a day off the bike would be the sensible option, so I caught a train to the town of Évian-les-Bains further up the southern side of Lake Geneva (or Lac Léman as it’s known locally). Évian-les-Bains is of course the source (or one of the sources) of the famed mineral water. It’s also a very expensive looking town with some lovely large homes, and a general air of prosperity. It sits across the lake from Lausanne, with regular ferries taking passengers across.

I headed to one of the sources where visitors can fill their bottles free of charge with the water. Indeed I saw locals carrying enormous jerry cans to collect litres of water at a time. In truth, I can’t tell the difference, although the water I drank there was lovely and chilled.

While I was eating lunch, I listened in to a group of Australians who were getting their rental bikes assembled in preparation for the next day’s Étape. They sounded eager, although I wasn’t sure looking at them, that they were all quite ready.

The morning of the Étape arrived, and I was up early to get some breakfast and make sure that I was ready to go in plenty of time.

The starting system means that riders are grouped into waves of about 1,000 riders at a time. I was in wave 3 out of 16 – having been allocated a fairly early wave on the basis of my performance the previous year. Waves are released every few minutes, but it does mean with the first (and fastest) riders departing at 7.00am, those right at the back don’t leave until nearly 9.00am.

That comes into play because there are time-cuts at various points along the course, and if riders don’t reach them in time, they’re put onto a bus and transported to the finish. They do this because many of the communities along the route would otherwise be cut off all day.

But this system does mean that those who are at the back are up against the clock from the outset if they’re not fast enough. It also means that the weather is warmer for them at various points along the route than it is for the earlier riders, on the basis that the heat tends to peak in the mid to late afternoon.

I got into my pen and looked around. Each rider has to attach numbers to their jerseys and bikes, and there is a flag indicating their country. That’s useful if you want to speak to another rider. The previous year, something had gone wrong, and I had a French flag. That meant that lots of people spoke to me in French – a language I can at best say I get by in, but would not claim to speak! This year, I had a Union Flag, but in my pen, there weren’t so many Brits around.

But I didn’t have long to worry about this before we were off.

The early kilometres of any mass participation event are a bit chaotic. Some people are patently in the wrong waves and are either much slower or much faster than others. This takes a while to level out, until finally there are no longer people overtaking and undertaking you at the same time. And nor are you finding someone with a bib number around 1,000 pootling along like it’s a Sunday social ride.

The early section of the ride was fine, and before I knew it, we’d crested the Col de Saxel and were speeding down the other side where we were almost immediately straight into the second climb, the Col du Feu.

I rode this quite steadily and it was still relatively early in the day, so the heat wasn’t too much of a factor, and around me, everyone seemed to be coping fine. On the descent I inadvertently dropped a couple of gels from my back pocket, but I’d brought plenty of nutrition, and I would be making full use of stops.

The organisers lay on various stops along the route, and while I didn’t need the first stop, which was mostly giving out liquids, I ended up replenishing my stocks at the others. I also briefly stopped at the two locations that Sports Tours had their own stops.

It was turning out to be a hot day – warmer than any other day I’d had during my week in France. So liquids were important. I also knew that I would be losing a lot of salt via sweat, so replenishing those salts via sports drinks would be vital. I tend to try to have one bottle with “mix” (as the pros call it) and one of water. It gives you variation, but ensures that you have what you need.

Now it was onto the Ramaz, and things were beginning to really get tough.

I was riding steadily, but I was beginning to see a lot of other cyclists stopping to catch their breath, cool down, or otherwise take a moment. I even saw a couple of people walking at various points. While it had been worse the previous year, I realised that I was theoretically with stronger cyclists this year being further towards the front. So it was more surprising to see walking already.

Water seemed to be a real issue, and I ensured that I drank plenty all the way through. I also tried not to waste it pouring it on myself. I relied on roadside spectators for that!

The best thing about the Étape is the crowds. While they were slightly fewer than in 2022 when many were already grabbing spaces for the Tour to come through a few days later, there were still plenty. And when they were offering to pour mountain stream water over your head, you just say “Oui!”

Kids with Super Soakers, cups of water, bottles of water, hosepipes, anything.

Once I was off the Ramaz and onto the final climb – the Col de Joux Plane – I was just in the zone. I was just grinding up in my smallest gear, that 34 tooth ring on my cassette being essential, and just pace myself slowly.

I just never want to stop because every time you stop it’s harder to start again. By now the sun was searing, but when it’s high above you, the shade is minimal. So it’s just a question of powering on.

Near the top of the Joux Plane I did feel very slightly woozy for a moment, but I downed a gel, drank some sports drink and continued.

The top was in sight, and for the Étape, the time taken would be at the summit. While there were a few more mostly downhill kilometres to go to the finish, organisers didn’t want people racing down a steep climb at the finish.

There wasn’t much on the top of the mountain, but I stopped for some photos, and spoke to a couple of other riders. A few people were just jumping fully clothed into a small nearby like.

The views were stunning, but I needed to get down into Morzine and the finish.

By the time I got into Morzine, I got plenty of food and drink, and talked things over with fellow competitors.

For those interested, my stats for the day showed that I cycled the 157km in 7:25, climbing a total of 4,144m. That was good enough to place me 3,307th of the 11,800 or so who finished the event. For my age category I was 317th out of 1524. I’m happy with that.

I burnt through 5,600 calories, and had an average power of 183W at an overall average of 21.0 km/h.

Perhaps the scariest figure I got from my bike computer was the temperature. The minimum temperature – at around 7.00am in the morning – was 18C. But the average was a heady 31C. And the maximum I experienced – at least according to my head unit – was a preposterous 45C.

Now, while that might have been a bit high, the thing I take from both this year and last year’s Etapes is that acclimation to the heat is really critical for the event. It really does get very hot indeed, and I saw people struggling all over the place on the hillside.

I had two quite large bottles with me on my bike and although that meant I had to carry extra weight up the climbs, it also meant that I was never going to run out of water.

One note of caution would be the person I saw at the top of the Joux Plane who looked like he’d come off. I asked him about his accident, and he said he’d been “taken out” by someone with a powerful hose who’d accidentally completely wiped out one of his wheels such was the power of the hose!

And remember, I was relatively close to the front of the event, alongside the theoretically fitter cyclists. Further back, it would have been even harder. Those cyclists would have been tackling climbs in the heat two or more hours after me.

What really makes this event are the people on the sides of the road. Some are locals, often essentially trapped by the event for the day, but out there cheering on the riders. Some are friends or family of other riders. Everyone supports everyone. At one point on the Ramaz, I was slowing a little and a pair of Estonian women (based on their flag), tipped water on me, and gave me a little push. I didn’t need it, but I wasn’t going to say no either!

Mercifully, I saw few accidents. The biggest problem that I saw with many people was the heat.

At one point, I group of guys passed me wearing Team Nigeria cycling jerseys. I don’t know if they were a national group, but I got a smile from them as I shouted, “Go Nigeria!” as they passed me, a couple of them at the front looking especially strong.

One of the things they always say about a region hosting the Tour de France is that it’s great for having roads re-laid. And that was true for this route. The roads were amazing, and it felt like at least two thirds of them were completely new! Coming from rough British roads, they felt wonderful to ride along, and there were no problems on the descents either.

Speaking of descents, that’s one area I’m always a bit circumspect about. Yes – I love a fast descent as much as the next person, but I don’t know how good my fellow cyclists actually are, and it’s about trusting in those riders if you go fast. So, I preferred not to be too insanely fast and ensure that I didn’t come off anywhere. But those descents are such fun!

Would I do the event again?

I’m not sure. The scale of it is massive, and having a challenge is something that drives me. But as I mentioned earlier in this episode, there are other events and climbs to do. Having done an Étape twice in the Alps, I’d like to experience some climbing elsewhere. And while we now know that next year’s event is in Nice, I might try something a little less formal – or at least smaller in scale.

I realise that I do like to have big cycling goals – they give me something to train for.

The Étape has been a fantastic event, and it’s well worth doing it. It’s well organised, and closed roads are fantastic. But there are lots of events and rides out there as well, and I think my 2024 objectives may be slightly different.