Introduction

Earlier this week, Google announced that their Google Podcasts app will be discontinued in 2024. They are instead pointing listeners to YouTube Music:

“Looking forward to 2024, we’ll be increasing our investment in the podcast experience on YouTube Music — making it a better overall destination for fans and podcasters alike.”

To facilitate this change, they’ll build a migration tool to let Google Podcast users transition to YouTube Music, much as they previously did when they transitioned Google Play Music users across to YouTube Music. Alternatively, using an industry standard OPML file, Google Podcast users will be able to move to a non Google-owned podcast app should they choose to.

In many ways, this is a good news for the podcast industry. It shows that Google is paying attention to podcasts again. I’ve often felt that Google has been the missing link in podcasts. Apple Podcasts is the most popular app, by consumption anyway, yet for a large part of the world, more consumers own Android phones.

But there are also many questions still to be answered about exactly how Google and YouTube are thinking of podcasts. My concern is that they think of podcasts as an adjunct to video. I’m going to delve into some of that in here, and lay out thoughts, concerns and opportunities that all of this could bring.

For at least the last couple of years, the position of YouTube in the podcast space has been of considerable interest to many in the podcasting community. And it has also lead to a lot of confusion.

Having spent the last few months thinking quite a lot about this, reading what others have written and watching talks, I still can’t say I know precisely where YouTube sits within the podcasting ecosystem. What’s more, I’m not completely sure that YouTube knows itself.

That’s primarily because the word podcast means different things to different people.

I have a joke slide that I’ve used on a number of occasions which has Socrates asking that most fundamental of questions: “But what is a podcast?”

The joke here is that to some people, if a podcast isn’t a file delivered by an RSS feed (in other words not freely syndicated across platforms, but exclusive to a particular platform like Spotify or Audible), then it isn’t actually a podcast. And there are many RSS true-believers who would argue that case strongly. At times, that might have included me!

Except that to the average listener, if it looks like a podcast, sounds like a podcast, and is called by all concerned a podcast, then it is, of course, a podcast.

For example, From the Oasthouse: The Alan Partridge Podcast is a paid-for title available exclusively on Audible. You cannot listen to it on Apple Podcasts. If you were nit-picking, you’d say it was actually a “comedy audiobook”, except that it sounds and feels podcast-y. So everyone calls it a podcast. (It even just won a silver award in the British Podcast Awards). Essentially, if it’s spoken word audio offered on demand, then it becomes a podcast to listeners regardless of delivery methodology.

And it’s this lack of clarity that does set the scene quite broadly for why I think YouTube and podcasts can create some confusion. Because now we have video too.

1. The Biggest Podcast Platforms

Let’s start by looking at a few research reports that list the most popular podcast platforms.

At the recent Podcast Show 2023 in London, Edison Research announced the upcoming launch of their Podcast Metrics United Kingdom, the first results of which have actually been published in the last week. One of the slides of their early findings shown at the event was this.

It suggests that in the UK, amongst 15+ weekly podcast listeners, Spotify is used for listening to podcasts by 45% of the population, BBC Sounds is used by 36%, and YouTube is used by 34%.

Unusually Apple Podcast was not shown on the slide, although you would anticipate that it would be in the mix there somewhere.

Well that’s clear then: “Spotify is the biggest podcast platform in the UK…”

Hold on just a minute, because this metric is just one measure of podcast consumption. What they’re actually showing is the number of people who listen to podcasts in the course of a week who listen to at least one podcast on that platform. It’s a reach figure. But it doesn’t measure the actual number of podcasts listened to.

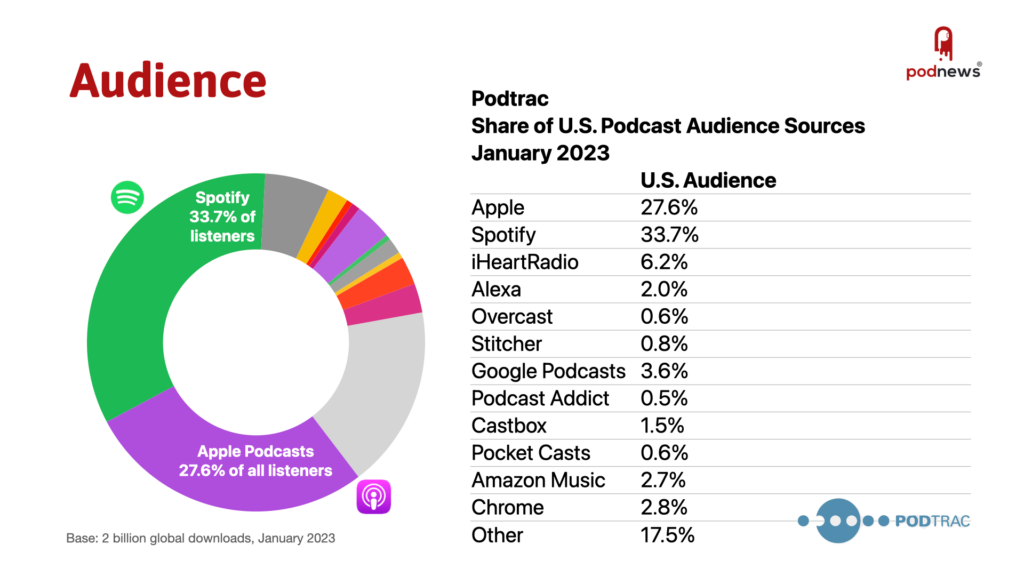

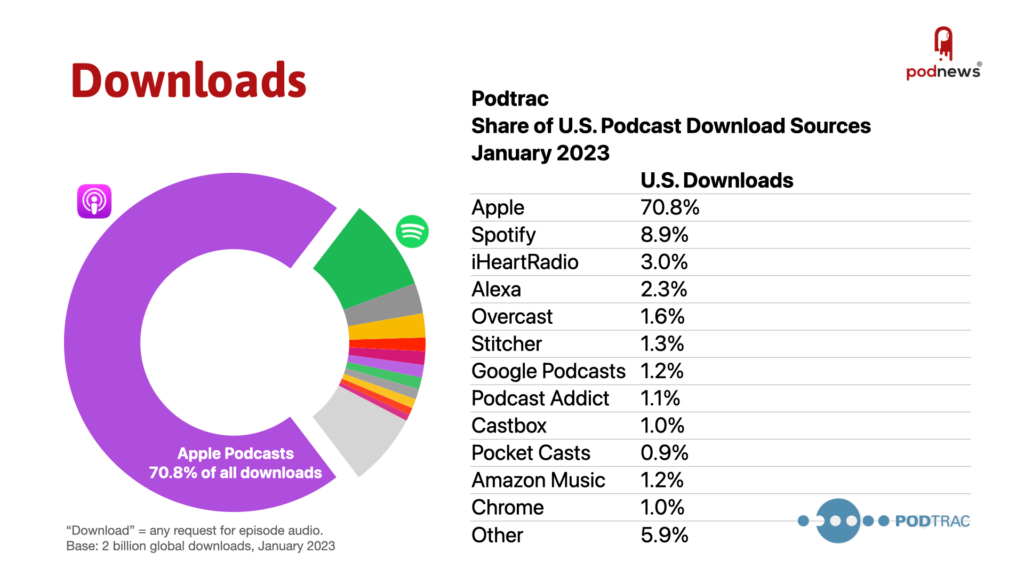

It may be that Spotify users, listen to fewer podcasts in the app, than Apple Podcast listeners do. Indeed, other reports suggest that to be the case. For example, Podtrac released some data at Podcast Movement Evolutions in Las Vegas based on podcast listening in the US, as reported by Podnews. It shows that Spotify has more listeners than Apple…

…but that Apple accounts for more downloads (including streams) than Spotify.

So, yes it’s true, more people listen to podcasts on Spotify, the sheer volume of podcasts listened to is greater on Apple Podcasts. For those who work or have worked in radio, this is the difference between reach and hours – or cume and share. Both are important – you can’t get hours without the reach. But commercially, the hours (or share) is more important because than indicates how many commercial impacts (i.e. adverts) you are able to deliver.

It also stands to reason that you might expect Spotify to reach more people. Podcasts are just one of Spotify’s offerings within its app. For many users, Spotify’s main use is almost certainly streaming music. Other forms of audio including podcasts and audiobooks are in addition to that.

If I open the Spotify app, I’m more likely to be thinking about listening to music, and maybe I instead find myself listening to a podcast.

If I open Apple Podcasts, the only thing I can do is listen to podcasts. Apple Music is an entirely separate app.

But while Spotify and Apple Podcasts are both, primarily, audio apps, when we move into the world of YouTube, third placed in the chart above, things get a lot more complicated.

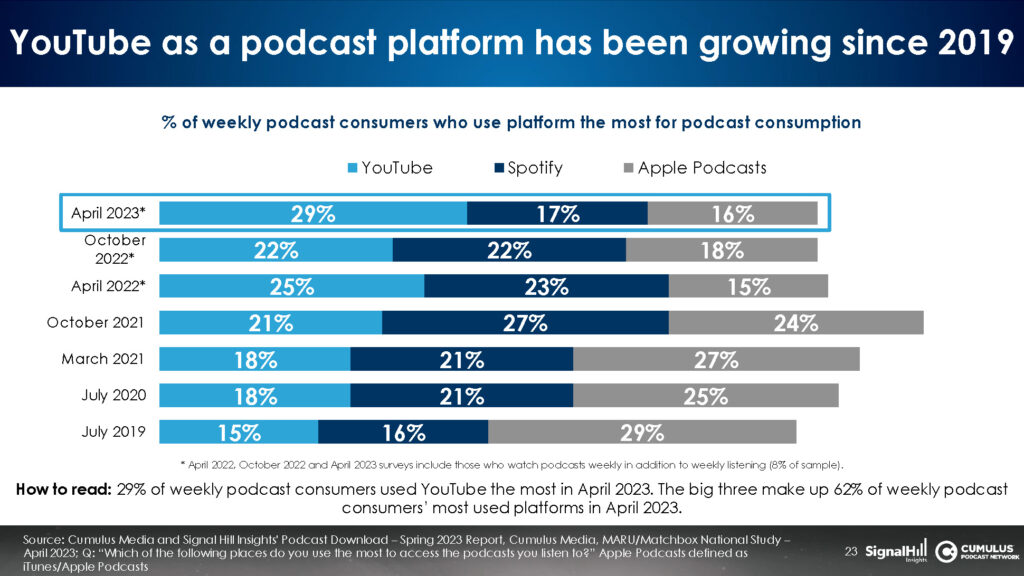

Earlier this year, Signal Hill Insights and Cumulus Media released their Podcast Download – Spring 2023 Report. The survey was conducted in April 2023, and represents the latest in a series of reports that shows how podcast platform consumption patterns have changed over time.

What Signal Hill Insights and Cumulus Media’s report says is that YouTube has now overtaken both Spotify and Apple Podcasts in the US.

But hold on!

The Podtrac research I referenced above does not even mention YouTube in their stats!

iHeartRadio, Alexa and Google Podcasts tend to be the next biggest, and they’re much smaller than Spotify or Apple Podcasts. How come Podtrac fails to even notice YouTube in their data?

And this is where the “What is a Podcast” question begins to get important. Podtrac’s methodology involves using an analytics prefix in front of the URL for the audio file in your RSS feed. As we will get into, YouTube does not currently utilise RSS feeds, so a company like Podtrac won’t be measuring any YouTube traffic at all. Instead, their numbers are based on the traffic patterns of their clients’ RSS feeds. And that excludes YouTube.

On the other hand, Signal Hill Insights and Cumulus Media’s Podcast Download Report is based on a sample of respondents who met their criteria, which include listening to, or watching (my emphasis), at least one hour of podcasts within the last week.

That means it would include things that call themselves podcasts, even if there is no RSS feed. As well as YouTube, that would include some Spotify exclusive titles (e.g. Joe Rogan), and listening on platforms like Audible (e.g. the aforementioned Alan Partridge title).

To summarise then, methodologies that are based solely around RSS feeds will usually entirely exclude YouTube because it doesn’t currently use RSS feeds. But YouTube listening to things everyone calls “podcasts” is actually pretty significant, regardless of whether they’re delivered via RSS feeds or not. And indeed, they may be accounting for more listeners than either Apple or Spotify.

I would again caution that the above chart from Signal Hill Insights and Cumulus Media, is measuring listeners and not listening. There may be more people overall who use YouTube for podcasts, but that does not imply that the overall volume of podcast consumption is highest amongst this group. Again, podcasts are only one small part of YouTube’s overall offering that includes everything from live streaming, music videos, as well as a plethora of other forms of videos.

From a consumer’s perspective, when I open the YouTube app, what I am hoping to get from it? There are many use cases, of which podcasts are but one.

2. Contradictory Evidence

In May this year, Bloomberg’s Ashley Carman published her weekly audio newsletter with the title “Massive Podcast Networks Put Their Shows on YouTube But Nobody is Listening.”

Her piece noted that in the US, YouTube had been making a significant effort to sign up podcast networks with partners including NPR, the New York Times and Slate going onto the platform.

From her piece:

Notably for YouTube, all three make up some of the biggest podcast networks in the US. By unique audience size, NPR is number three on Podtrac’s top podcast publisher ranking for April. That month, its 49 active shows generated more than 168 million global downloads. The New York Times came in at number four. With only 12 shows, it managed to rack up over 111 million downloads. Slate doesn’t participate in the tracker but said it had accumulated 190 million downloads last year, a sizable number, albeit not on the same scale as the Times and NPR.

So these are all big podcast networks in other words. But Carman goes on:

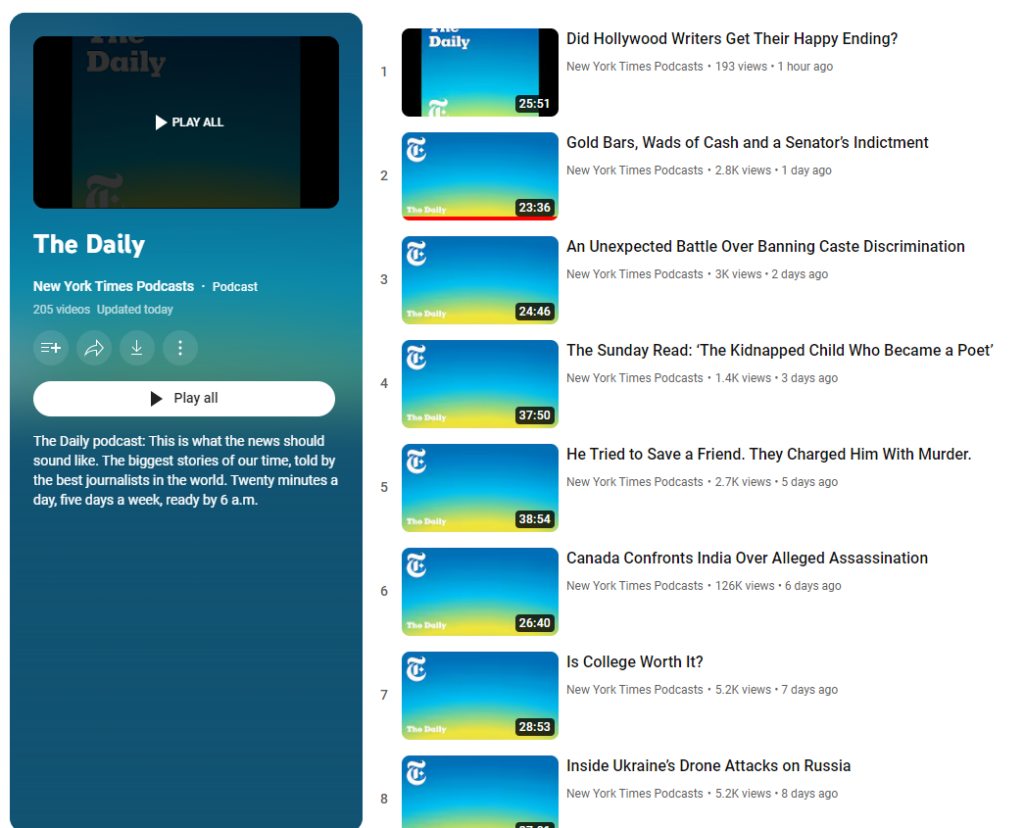

But despite their impressive reach elsewhere, these networks’ podcasts aren’t doing so well on YouTube. Slate’s shows averaged around 75 views per video over the past week while NPR was around 179. The New York Times performed slightly better, especially The Daily. But that show, one of the biggest in the world, still only received around 1,000 views on average over the past week.

And indeed, while that was now several months ago, I went back to have a look at how things are progressing more recently.

Here’s the latest episode of the Slate Political Gabfest, one of Slate’s most prestigious and long-running titles. The most recent regular episode was published five days prior to this and it has achieved just 196 views on YouTube.

The New York Times’ The Daily does better, achieving between 3,000 and 5,000 or so “views” for each of its episodes. (The first episode below is only an hour old at the time I took the screengrab, and I would note that the episode over the ongoing Canada/India alleged assassination is a massive outlier here with 126,000 views.)

But even these four digit numbers are not impressive. The Daily is one of the biggest podcasts in the world. Things clearly haven’t moved on from when Carman wrote that piece earlier in the year.

It should be said that all three outlets were uploading audio-only podcasts, and the Bloomberg piece notes this. There is little for viewers to actually see here. In the case of the New York Times, it’s literally a still of The Daily’s cover art. For Slate, they use audiograms to lightly animate their offering over a generic still background. Audiograms are those audio-waveform patterns you often that mimic what audio looks like in an audio editing environment, and there are tools that allow producers to spit out audiograms of their output automatically, or with relatively low production cost.

Of course, there is a massive difference between making an audio-only podcast like The Daily which may have correspondents or reporters all over the world, and mix many kinds of audio elements together, compared with something that is closer to a TV panel show.

And while the New York Times could certainly put a camera in front of their presenters Michael Barbaro and Sabrina Tavernise, and edit in Zoom contributors from all over the world, for all I know, their presenters may frequently record in a home studio, and that might break the illusion a little. Watching someone occasionally interjecting, “Haaa…,” whilst listening to an audio-only contributor from somewhere far away, isn’t likely to be the most compelling visualisation either.

But on the face of things, this does all make for a curious anomaly. Some of the biggest podcast titles in the US are available on YouTube, but they’re registering just a relative handful of views.

On the other hand, research suggests that YouTube is perhaps the single most popular app for consuming podcasts.

What’s going on?

3. What Is A Podcast on YouTube?

Let’s start this by saying what it is not. It’s not audio delivered via an RSS feed.

At this moment in time (September 2023), you cannot simply give YouTube your RSS feed, and expect it to deliver audio to its users in the same way that you might to Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

RSS feeds usually work on a pass-through basis. When you click in your app to stream or download an episode of a podcast, it doesn’t usually come directly from Apple or Spotify’s servers, or indeed, those of other podcast apps.

Instead, your app of choice (“podcatcher”) will use a URL in the RSS feed and fetch the audio from there. This URL usually terminates at your podcast hosting company, and there are perhaps hundreds or thousands of them. You might even host your own podcast – especially if you’re a large corporation.

That has multiple benefits for all concerned. If I hit “play” on an episode of The Daily in the Apple Podcasts app, the audio is fetched direct from a New York Times controlled server and played back to me. Apple does not keep a copy on its own servers. This means that the New York Times can dynamically serve me ads based on where in the world I am, and when I’m listening. It can potentially also use other identifiers it may have about me, such as whether I’m using an iPhone or Android device to listen and so on.

From Apple’s perspective, there are no expensive hosting fees to worry about, and perhaps more importantly for them, they’re not responsible for directly serving any of the actual content of the audio. If there’s a commercial music track in the podcast that shouldn’t be there, or someone is being libelled (or slandered), then Apple has some deniability. (NB. I am not lawyer, so do not take legal advice from me on these things!).

This delivery method also means that your podcast host has the most complete picture of how many listens or downloads you’ve achieved. Because no matter which podcatcher your listeners choose to use, they all have to collect their audio from your podcast host’s servers.

Sidenote: In cases where Apple is offering podcasts via a subscription, then the audio is being served direct from Apple and not via an RSS feed. Similarly, Spotify hosts its exclusive titles like Joe Rogan directly from its servers. And of course titles hosted on Spotify for Podcasters (formerly Anchor) are coming directly from Spotify owned servers.

But for YouTube, things are different. Currently, that means either uploading a video version of a podcast, or for some partners, providing an mp3 audio file, but it all being hosted by YouTube.

The provider uploads once, and YouTube is responsible for all the delivery. Indeed, YouTube is the only person who actually knows how many listens there are to an episode, since it is only YouTube’s servers that have that data.

It’s probably worth acknowledging here that while YouTube’s podcast offering is changing quite quickly, the full podcast experience is at time of writing, only available to users in the US.

Things do seem to be changing rapidly, but as of September 2023, YouTube hasn’t really begun to roll things out globally.

I would suggest that there are essentially three types of podcasts on YouTube. And depending on the kind of podcast you’re hosting on YouTube, I believe it probably makes a significant difference to your audience on that platform.

I also think that depending who the podcast creator is makes an enormous difference, but we’ll return to that later.

Note that I am definitely generalising here, and I’m sure that there are overlaps between many of these formats.

i. Stills-Based or Audiogram Podcasts

These are the simplest podcasts, and are essentially a lift-and-shift of audio into the YouTube environment.

These are titles that have been made in an audio-first production environment, and relatively little work has been done to “visualise” the audio. Instead they will commonly use audiograms to provide some kind of moving image, if any at all.

Alternatively, there may be some very simple motion graphics that can be stretched or looped to any podcast duration and provide some kind of visual wallpaper to supplement the audio.

In general terms, these videos are not made to be watched, but instead listened to in the background. However, because YouTube is (at least mostly) a video platform, productions uploaded to it need to have some kind of visual element to accompany the audio.

They may have been animated, utilise stock imagery or other clips, and are generally offering not much more than a wallpaper to look at.

The New York Times’ The Daily podcast simply has a still image.

Slate clearly labels their Political Gabfest podcast as Audio Only, but has an audiogram at the bottom.

HBO’s Succession podcast with Kara Swisher is audio only, but uses various “establishing” shots from the series as a kind of visual Succession wallpaper whilst you’re listening. Note that there are not any camera shots of Kara or her guests.

Of these three podcasts, I would note that the Succession podcast has done significantly better than either of the other two. But this is a title that sits on the main HBO YouTube channel – a channel with nearly 3m subscribers. The rest of that channel is mostly full of trailers, behind the scenes clips, interviews and so on. It’s also the most visually appealing, although those clips loop around quickly.

The other two titles sit on YouTube channels that have fewer subscribers or comprise mostly of audio-only titles.

Yes – the Succession TV series is a pop-cultural phenomenon, and I picked the accompanying podcast of the final episode. But I think placing an audio-only podcast on a primarily video-only YouTube channel is undoubtedly going to give a podcast title a step up.

ii. Visualised Audio-Only Podcasts

These are titles that have been made in an audio-first production environment, but have had significant post-production work done to them to make them also visually engaging. As such, they’re probably the rarest of the three types of podcasts I’m exploring here.

This type of production lends itself to titles that are not simply people sitting in a studio talking to each other, but are factual podcasts that incorporate interviews, voice-overs, soundscapes, music and so-on.

Doing this well can be more expensive, as you need to think of creative ways to illustrate the audio, but some effort is being made for each scene of the podcast. Sometimes interviews may have also been recorded on video which eases the process, but it’s rare that someone has made a full video documentary and audio podcast without producing different versions of the production for each medium.

There is obviously an overlap between the Succession example I showed above and something like the example below.

The BBC World Service animated a clip from an episode of 30 Animals That Made Us Smarter. This excerpt is part of an animation showing how a kingfisher inspired designers of Japanese bullet trains avoiding making loud boom sounds.

iii. “On-Mic” Video Podcasts

The archetypal of these kinds of podcasts is a video of the presenters, probably in the same room, or sitting on a set together for each episode, often with microphones very visible (Think of a Shure SM7B microphone on an articulating arm), but being professionally filmed on a multi-camera set-up with full lighting.

These video podcasts are frequently podcast “spin-offs” made by presenters who would consider their day-job as regular YouTubers, rather than podcasters moonlighting as YouTubers. As podcasting has grown a significant number of YouTubers have added podcasts to output, and they tend to think video-first because that’s what their output is built upon.

The main difference is that whereas their regular YouTube channels would normally be built around tightly edited and post-produced videos, the “podcast” versions are often a bit more freewheeling and have less post-production. They’re probably less scripted, working off a running order instead for a more conversational tone. Those with larger operations are probably employing someone off-camera to direct the show and they may be using software like OBS to cut between cameras. Indeed, they may also broadcast their podcast live on YouTube and/or Twitch, incorporating listener comments on those platforms, in addition to making it available later on-demand.

Remote guests might be joining via video-conferencing software like Zoom, although video will be as important as audio, rather than audio-first software commonly used by podcasters such as Riverside.

This kind of podcast is often used by TV broadcasters who are able to produce something that works in both audio and visual spaces.

The key thing with this type of podcast is that the producer’s prior audience has been built on visual videos [sic], and not from an audio-first perspective. Podcasts are a spin-off of their video output.

The WAN Show from Linus Tech Tips is a great example of YouTubers doing podcasts. To be clear, this has been around a long time – perhaps as far back as 2012. And despite the duration of over 3.5 hours, this episode has achieved 618,000 views in just three days (Although video metrics are themselves a whole other discussion). That’s obviously built on Linus and the team having one of the biggest tech channels on YouTube. Note that 15.5m subscribers still doesn’t crack the top 50 for YouTube though, which is headed by the Hindi music channel T-Series with 244m subscribers (Mr Beast is at #2 nearly 83m subscribers behind).

An example of a broadcaster doing a visual podcast is Sky Sports and their Sky F1 Podcast. It’s very much a visual affair. It also gets shown on Sky’s F1 TV channel. Note that, I suspect for rights reasons, there are no actual clips of racing.

Here’s an example of someone who’s predominantly a YouTuber entering the podcast space. This was only their second episode, but it had clocked up 45,000 views in the first five days. Note that it has runtime of over an hour, for a channel where most regular videos would probably be tighter 8-15 minute episodes.

It can also be noticeable that when YouTubers turn to podcasts, they’re often referring to visual things, pulling faces or pointing, leaving the audio-only listeners will be missing things. That’s something that tends to take time to get used if you’re not coming from an audio-only background.

To be completely fair, there are now many audio-first podcasts that are recording in studios with camera set-ups so that they can reach YouTube audiences as well.

The Vergecast has relatively recently added video to the mix, with the regular presenters sometimes being together in the studio, but usually one or more is remote.

On the other hand The Media Podcast with Matt Deegan has recently moved to a mostly studio-only set-up. (Disclaimer: I’ve appeared on this).

And it’s certainly now the case that more podcast producers are demanding camera facilities from podcast recording studios that they use, and many of those studios are now equipped with some level of camera offering.

Bonus Category – Clips

There is a fourth category of YouTube podcasts – the clip package. This could be any of the first three, but instead of providing the full podcast, it is presented in a more snackable form for shorter YouTube views. These clips don’t just appear on YouTube of course – TikTok and Instagram are also important destinations for them. And these might be podcast clips from videos that are platform exclusive.

Joe Rogan would be the exemplar of that:

But there are plenty of others that Spotify especially pushes.

Most of current Wrexham Town goalkeeper Ben Foster’s The Fozcast podcast excerpts on YouTube come with this intro reminding viewers that the full show is available on Spotify.

And the BBC used YouTube to promote its Match of the Day: Top 10 podcast which was available exclusively on either BBC Sounds (in audio) or BBC iPlayer (for visuals).

4. What Are the Upsides of YouTube?

There are a few key reasons that people are using YouTube, and they really depend on who is making the podcast.

i. YouTube is Massive

I think that’s kind of obvious, but YouTube is second only to Google in size, and as a consequence it’s also the second biggest search engine on the internet. That is very helpful if you want your podcast to be discovered.

If you want to get your output in front of as many potential people as possible, being on the biggest media distribution platform on the planet is probably a good idea.

ii. Audience Expectations

If you’re starting a podcast from scratch, you need to think carefully about who your audience is, why they might listen to you, and what kind of person they’re likely to be.

If you already have a substantial YouTube audience and you’re entering the podcast space, then it makes enormous sense to leverage that audience and for your podcast to be shot on camera, on a fixed set, but also be made available in an audio format via the usual platforms.

It’s likely that the bulk of your audience is going to come from YouTube, and it’s entirely possible that most of your listening will also be on YouTube.

To a large extent, the fact that you’re making a podcast is neither here nor there. In fact, it’s just another video, but published in a different, probably looser, format. Instead of an 8-15 minute video, it’s more likely to be an hour or more. And the fact that the podcast is also available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and everywhere else, is a bonus, potentially allowing you to reach audiences that you can’t reach via YouTube.

iii. Target Demographics

You also need to carefully consider who your target audience is. How old are they? What else do they listen to or watch?

While every demographic is a YouTube user these days, unquestionably the platform skews younger than the population, so if that’s the audience that you want to reach, then YouTube makes sense.

iv. Podcast Format

But none of this really works unless your podcast is, broadly speaking, a studio-based discussion-formatted title. If it is, then going on YouTube almost certainly makes complete sense; indeed you should probably have some good reasons for not going onto the platform.

Get your presenters to sit in front of microphones, some laptops for running orders and live Googling, and away you go. Some basic lighting and perhaps a single camera is all you need at a minimum and you’re away.

But if your podcast is investigatory, has hand-crafted soundscapes, is a drama, or is trying to take you away to another place, then perhaps YouTube isn’t right for your title. At least fully visualising it isn’t anyway. Even a basic one-to-one interview format might be damaged by adding video to the mix. Perhaps the interviewee feels more comfortable in an audio-only format and is likely to open up more?

I’m not sure that YouTube really has a ready solution for this kind of podcast. But I’ll return to this issue shortly.

5. What Are the Downsides of YouTube?

i. Cost

Cost is the biggest issue. In many respects, podcasting has been enormously democratic – you can start one with just a smartphone and have it online within minutes. While I would suggest investing at least a modest amount on money on some microphones, and spending a little time with some audio editing software to tighten up whatever you recorded, the fact it is that this can all be incredibly cheap. And if you’re careful, you can sound really good, even without a fancy studio that eliminates exterior sounds.

If you also need to video your podcast, even a simple conversational, studio-set title, you need half-decent cameras. You’ll need at least one, ideally two, and quite possibly more depending on the number of guests. A basic set-up might mean having a wide camera showing everyone, and then some locked-off cameras focused on each presenter. Fancier productions will utilise more than one camera per person, and more than one wide shot to keep visual interest high.

Then you will need some set-decoration. If you’re lucky, your studio will use screens like those used by The Media Podcast in The London Podcast Studios above. They allow a production to personalise those LCD panels scattered around the studio, and perhaps change the lighting to match your branding. Ah yes – lighting is another cost. You will need some studio lights.

If you really want to look good, then that microphone arm you’re using may not be good enough since it might block camera angles, so you’ll need to invest in low-slung arms that don’t get in the way.

It must be said, however, than many YouTube podcasters do like to show off their microphones in vision – especially if they’re using Shure SM7B microphones which seem to be YouTuber’s – and Twitch streamers’ – podcasting microphone of choice. (There are plenty of other options – don’t feel pressured into a single model. It might not be right for the sound of your production, or the sound of your voice.)

Then you’re going to have to vision mix the whole thing as well mixing the audio. It’s noticeable that many On-Mic Video Podcasts run long, and don’t have much in the way of actual editing. In other words, they’re recorded as live, or indeed first went out completely live. The only “editing” is someone choosing between camera angles. Ideally, that’s an extra person, but there are various automated ways to do it, utilising software to determine which microphone is being used, or indeed, if none are, switching to a wide shot.

Someone good with a StreamDeck and OBS might be able to multitask and switch between cameras themselves, but that’s hard to do while you also think about intelligent things to say at the same time!

At the recent Podcast Show in London, I attended a session that focused on the Waitrose-branded Dish Podcast with Nick Grimshaw and Angela Hartnett. What became very apparent was that this was a fully produced TV show that just happened to be a podcast. They spoke in great detail about the care and attention they gave to the video side of things.

The production values are extraordinarily high, with a full studio where they prepare the food and present it to that week’s guests, while there is also a food prep area off camera.

It would be fascinating to learn what the production budget of this series is (or was).

[That all said, I couldn’t help but notice that only a few older episodes seem to be on YouTube. Have they stopped videoing it of late?]And critically, you really need someone to edit down your show. That becomes a bit more complicated if you’re mixing for video and audio. In the audio world, removing pauses, “errs”, irrelevant parts of the conversation and so on, can be done very tidily. The listener shouldn’t even notice. With video, it’s more complex. Edits can be very obvious unless you’re able to cut away to something else, and if you’re not careful, you end up making the whole thing twice – once for audio and once for video.

ii. Visualisation May Be Wrong For Your Format

If your podcast is not studio-set or falls into a different non-conversational genre, then a straightforward “to-camera” approach might not be right for you at all.

Audio dramas are a great example of that. Drama is significantly cheaper to make if the audience is conjuring imagery in their minds, rather than you spending tens of millions on elaborate sets, locations and fancy VFX shots!

An investigative documentary series might not work very well without a full camera crew in tow, which means your budgets are suddenly vastly bigger. At this point you’re making a TV documentary.

Even a straight news podcast might be a more complex beast, and again you might end up making a TV news programme rather than an audio news programme.

It’s entirely possible that there is a podcast that’s delivering some gangbusters numbers on YouTube whose only form of visualisation is a still image or an audiogram. But I’ve not seen it.

(Update: On Twitter/X, a commentor shared a couple of YouTube channels that broadly only have still images, but which are collecting very decent “views” on the platform. With the proviso that a “view” on YouTube is only 30 seconds.)

As some of the numbers discussed above show, to date, YouTube just doesn’t seem to work for audio-only titles in any meaningful way.

6. Where Next For YouTube and Podcasts?

YouTube is an interesting and evolving beast.

It’s worth noting that there are two core parts of YouTube, although there is an overlap between them both.

- The regular video side of YouTube that everyone is familiar with.

- And YouTube Music, which can essentially be thought of as Google’s Spotify competitor. It’s an audio-first app that currently mostly has music on it.

Sidenote: I’m ignoring a third form of YouTube – the Virtual MVPD side of things, YouTube TV. In the US this acts as an internet-delivered version of your local cable bundle. And YouTube TV’s recent deal with the NFL to licence their “Sunday Ticket” package is an interesting development in this space. However, to date, YouTube TV has not extended beyond the US.

Outside of these two is Google Podcasts, a product that hasn’t had a lot of love shown to it for a while, and which we now know will be retired next year (It is being “sunset” in the industry parlance).

In that respect, Google/YouTube is following the precedent set with Google Play Music their original music app which was killed to make way for YouTube Music.

Now YouTube is beginning to lean into podcasts as a growth area for the platform, and they’re doing so across both YouTube and YouTube Music.

In the US, they’ve already launched YouTube.com/podcasts as, what effectively seems to be a placeholder part of YouTube where any videos that call themselves podcasts are gathered together. These are not RSS feeds – but videos that are uploaded into regular YouTube channels, using the same Studio backend as exists for regular YouTube videos.

Right now when you upload, YouTube is expecting a video file – hence the need to in some way visualise your audio in one of the ways listed above.

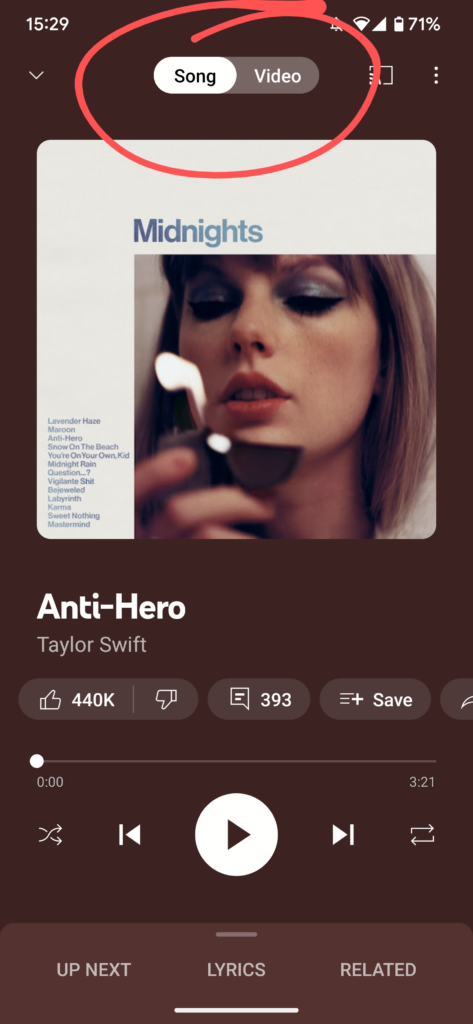

Podcasts do seem to slot into both YouTube and YouTube Music, with an awareness that most of what users do in YouTube Music is listen to something. That said, in YouTube Music when you listen to a song that YouTube has a video version of, you’re able to hop over to the video and watch the song instead.

YouTube does seem to be getting excited by the opportunities they can afford podcasters.

i. YouTube, Android and the GMS Suite

I’ve long thought that one of the key reasons that Apple dominates so much of podcasting, aside from its strength in the US market, is the fact that it has always offered a default podcasting app on its devices. If you buy a brand new iPhone, it comes with a group of default apps including Apple Podcasts.

As a consumer, if I want to learn more about these podcasts that I’ve been hearing so much about, I open the Apple Podcasts app and I’m off to the races.

With Android, that’s really not the case. Some manufacturers may include a podcast app. And yes, Spotify does deals with mobile operators to have its app pre-installed. But Google Podcasts was never pre-installed on every Android device – at least not as a default app.

When phone manufacturers install Android and want to use Google’s services they have to agree to take the Google Mobile Services (GMS) “suite” of apps. Basically this means that if a phone manufacturer wants to offer YouTube, Chrome, Gmail, Google Maps and the Google Play Store on their phones – and they probably do – then they’re required to offer the full stack of the GMS Suite.

While the rules can vary by jurisdiction, as can the apps that are included, YouTube Music is amongst the list of apps that are included in that suite and are therefore pre-installed.

Having an app that delivers podcasts pre-installed on every phone in the world is powerful for growing podcasts. It means that the first thing a consumer with an Android phone who wants to know about podcasts is no longer scroll down a vast list of mostly unrecognisable podcatcher apps on the Play Store, but use the one that’s already on their phone.

Sidenote: Yes the default apps on phones aren’t the best. No, of course I don’t use one of them.

ii. Monetisation

Ultimately, YouTube is about monetisation and YouTube is thinking a lot about that. They’re going to launch audio advertising at some point which they will sell into podcasts. I assume that there is also the potential for them to launch a competitor to the Spotify-with-ads music service as well if they fully lean into audio ads.

But YouTube is mostly thinking about the adverts that they are able to sell into podcasts that sit on their platform.

7. Unanswered Questions – September 2023

So far, it does feel that YouTube is retro-fitting its enormously sophisticated video platform to accommodate audio. Their thinking is very much coming from the video world. If you upload a podcast to YouTube today, you put it into a “Channel.” They have tools to link clips (or “Shorts”) with the full-length video it came from. They are well versed on what kinds of thumbnails will work well for titles on their platforms – although they’re going to be expecting 16:9 ratio images not the tradition podcast squares. In a YouTube environment, show and episode artwork probably need to be very different from what will work for you in Apple Podcasts or Spotify!

There are benefits to all of this. Things like comment moderation are probably the best available, and if you need to do something like geo-block, YouTube is streets ahead of most other platforms.

But YouTube is a video platform first and foremost. And there are a few key questions still outstanding.

i. RSS Ingestion and Integration

If someone, somewhere has fully explained how this will work, then I apologise. But despite looking, I’ve not found the answer.

Everything about YouTube and podcasts to date has involved the podcast producer uploading a copy of their title, probably in a video format, to YouTube. YouTube hosts that video, and offers analytics via their regular, very sophisticated platform.

But that’s not how the rest of the podcast industry works. Most use some kind of podcast hosting platform, and for the fullest picture of your title’s performance you use the analytics platform of your podcast host to get the fullest view of it. Yes, you might also claim your title on Apple’s Podcast for Creators platform, and Spotify’s equivalent. Each of them offers their own bespoke measurements about consumption on their respective platforms, including extra information that your podcast host can’t offer.

But your host does still have a complete overview of all consumption. Nobody else can offer that.

Now YouTube is talking about ingestion via RSS feed, but it’s not clear what that actually means.

Is there an audio pass-through to the originating host? Or does YouTube just download a single copy of your podcast and then serve it directly from YouTube’s own servers?

Remember that to date, YouTube is only serving video directly from their own servers (or audio in YouTube Music’s case). That ensures that everything is under their own control. My suspicion is that it would take some significant re-engineering to accommodate passing through audio from third-party hosts as traditionally happens with podcasts. On the upside, audio files are small compared to 4K HDR videos.

The other key thing that using a podcast host that is not YouTube itself allows is control over your own monetisation. Which brings us to the next point.

Non-Google Monetisation

Everything I’ve seen and read so far about YouTube and podcasts has spoken about the YouTube monetisation offerings that they will be providing. The pact you make with YouTube when you upload a video is that they can sell advertising around your video and, if you’re big enough, you can share that revenue.

But with podcasts we’re talking about an industry that already has monetisation structures in place. A decent sized pre-existing podcast might be selling their own advertising and sponsorship opportunities and integrating them into their title. They might also be working with third-party sales partners who sell advertising on the title’s behalf. With the very biggest titles, these are significant sales opportunities – different sales partners might offer big incentives like minimum guarantees to attract podcasters to work with their company.

And you would think that these deals come with certain expectations of sales exclusivity. If a podcast sales company is offering me healthy return for my podcast, then they may not want me cutting separate deals with YouTube that allows them to sell advertising around my title as well!

In any case, with dynamic advertising a growing part of podcast advertising. This is the technology that dictates precisely which advert will be embedded into the audio file that an individual listener hears. This would not seem to “play well” with YouTube just ingesting a single copy of podcast into their system.

Here’s an example. My podcast has an agreement with a sales house to sell dynamic advertising into my podcast. The sales house use factors like geography and the date and time I download a title to determine what ad a listener gets. So a listener in New York today gets a very different ad to a listener in London next week. But in a world where YouTube takes a single copy via RSS, then my podcast sales company delivers a single ad into the file, with geography and time dictated by when YouTube scraped my feed!

Here’s a practical example. If I listen to the most recent episode of the Slate Political Gabfest podcast here in London in a regular podcatcher app, the first ad I’m served is for Salesforce, and is voiced in British English. It’s targeted at the UK, and was probably sold locally by Slate’s sales partner. If I listen to the same episode on YouTube, I instead hear an ad for PhRMA, a US company with copy that is irrelevant to me as UK consumer. And because it’s “baked” into the audio, everyone will hear the same ad on YouTube. That Salesforce ad I heard via RSS might be something entirely different for you depending on when you listen and where you are at the time. Note that this is separate from any YouTube enabled pre-rolls or mid-rolls. And speaking of which…

How will mid-rolls work? Podcasters often carefully determine where the natural point for a mid-roll break (or breaks) might be. How does that work via RSS? Should there be additional flags in the metadata? Will AI solve the problem?

It’s certainly true that some YouTube video creators mix and match a bit, baking in their own sponsor deals in addition to allowing YouTube to further monetise those videos with their own ads. This is common in “Tech YouTube” where videos quickly throw to a sponsor early on. And massive YouTubers like Mr Beast have integrations negotiated outside of anything YouTube is doing.

But that’s in a world where YouTube is essentially the only way that consumers can access those videos (excluding premium offerings via Floatplane, Nebula and others).

Podcast monetisation has been built so that it works on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Castbox, Pocket Casts and “wherever you get your podcasts.” Will YouTube and YouTube Music play nicely with this system?

Summary

There is a massive opportunity here. YouTube and YouTube Music potentially can give a bit of kickstart to many of those who have yet to start listening to podcasts. Recall that even in the US, where podcasting is perhaps most established, only 42% of the population listen to a podcast each month. That means that 58% of the US population don’t regularly listen to podcasts.

And that number is significantly higher in other parts of the world that have smaller podcasting ecosystems, and are likely to be more dominated by Android phone ownership.

But I’m not sure that YouTube properly understands podcasts from an audio perspective. I’d really love to be proved wrong on this point, but everything they’ve talked about so far comes from the perspective of creators who currently make videos now leaning into podcasts.

YouTube’s experience of podcasts is they are best served by those who have a visual element to them. And some of those numbers above would suggest that to date, they’re not wrong. But that is to ignore the use case of audio.

Consumers are not always available to view a video feed. When you’re driving, running, walking, cooking, washing, working out, cycling, working, sleeping even – you frequently don’t even have the ability to watch something at the same time.

Maybe in some far flung Elon Musk fever dream of a world where we’re chauffeured to work in our driverless cars, or leave the washing up and laundry to our household robots, we’ll have more time for video screens. But right now there are multiple parts of our days when audio is all that we can consume concurrently with the rest of our lives. And I’m not sure YouTube fully understands that. Or if they do, they’re not really chasing that part of the ecosystem. In which case, that’d be very disappointing.

Sure, there are those secondary viewing experiences. Perhaps the YouTube video is playing in a different tab in our browser letting us flip back from time to time, or the video podcast playing on our Google Nest Hub in the kitchen can be glanced at from time to time while we’re doing the dishes. It’s not an all or nothing.

But then there are the vast range of podcast formats that just don’t really work in a video space – at least not without significantly increasing production expenses.

I really want to see podcasting grow beyond where it is today. Audio remains an important medium – working in so many environments that viewing doesn’t work. It’s just wrong to think that audio could be made just a bit better if you added some pictures!

Google, YouTube and YouTube Music really have an opportunity to drive forward audio listening globally and not cede the whole space to Apple and Spotify. I know it’s probably hard for them to think that way – they’re coming from a position of complete dominance in the video space. Sure there is Netflix, but they’re playing a different game. YouTube doesn’t even have to pay for its content!

As I say, I would dearly love to be proved wrong on much of this. I see YouTube’s serious entry into podcasting as a massive benefit, but I also know that things that don’t move the needle at Google can quickly get side-lined (Google Reader anyone?).

Time will tell, and perhaps anyone who reads this in twelve months time will be laughing at my misgivings that haven’t come to pass. I hope that’s the case.

I will be watching – and listening – eagerly.

Updates: Removed a reference to YouTube only podcasts because although I’m sure they exist, I can’t find an example right now.

Disclaimer: As always, these are my own views, and do not represent those of my employer. You knew that anyway, but I like to spell things out.